History has a mischievous habit: it doesn’t die; it merely changes costume.

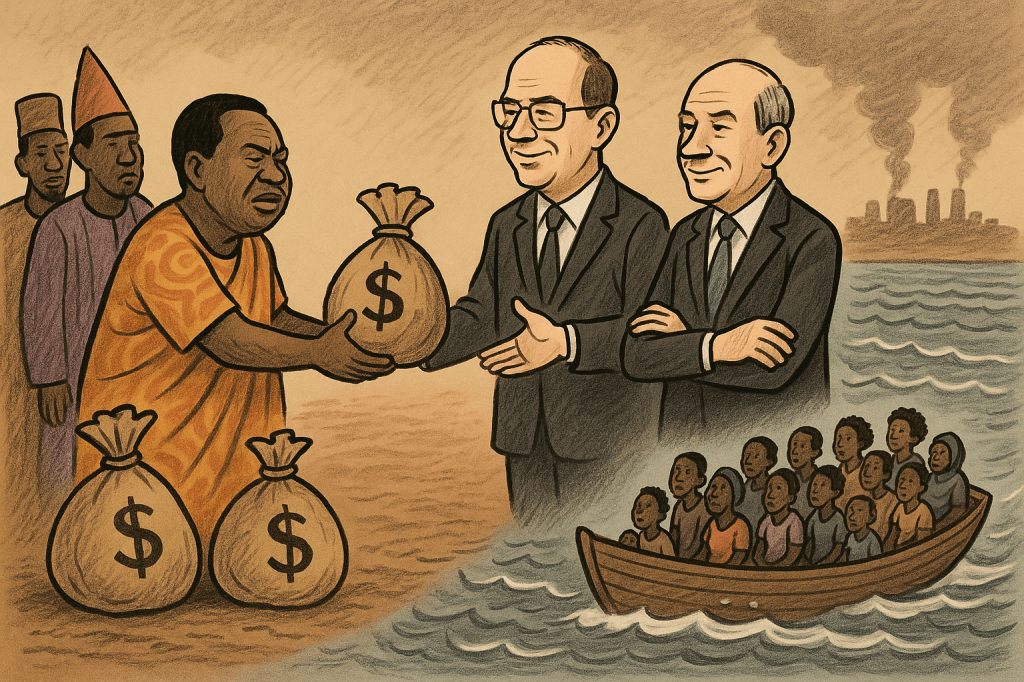

The transatlantic slave trade, we are told, was a wicked two-man show — the European buyer and the African victim. But there was always a third actor lurking backstage: the African collaborator, the merchant-king who sold his neighbours for beads, gin, and a thunder stick.

Fast forward three centuries, and the stage props have changed — the ships are now private jets, the trinkets are Swiss accounts, and the middlemen wear imported suits with matching moral bankruptcy.

Yesterday’s Traders, Today’s Leaders

Yesterday’s African traders sold their own for guns and mirrors; today’s African leaders sell their nations for loans and policy papers.

They plunder their countries’ treasuries, stash the loot in Western banks, and then fly out to attend “Economic Summits” where they are politely lectured on governance by the same institutions that help them hide their spoils.

From London to Geneva, from Delaware to Dubai, the modern equivalent of the slave ship’s hold is the numbered bank account — the vault where stolen African wealth sleeps while its owners beg for aid.

The Western Partners in Crime

The Western governments and financial institutions play the same role their ancestors did — they buy the goods and pretend ignorance of the source.

In the 18th century, it was human cargo from West Africa; today, it is crude oil, gold, lithium, and stolen public funds laundered through “investment portfolios.”

They advise African leaders to “tighten fiscal discipline” while ensuring that their own economies benefit from African chaos. They smile through IMF frameworks and World Bank policy blueprints — politely demanding “structural adjustment,” which is the modern word for economic kneeling.

And the African People — Still Paying the Freight

The African people remain the cargo, not in chains but in queues — at embassies, airports, and border fences.

Every year, thousands risk death across the Sahara and the Mediterranean, seeking a better life in the very lands where their ancestors were once sold.

It’s poetic injustice: the descendants of those sold now volunteer to go back, not chained by iron but by economic hopelessness.

The new slave ship is the rubber dinghy, the new plantation is underpaid labour in foreign lands, and the new master is the global economic order that thrives on Africa’s perpetual instability.

The Modern Triangle Trade

The geometry of exploitation remains triangular:

African rulers loot their people and send the proceeds abroad. Western institutions receive the loot, then offer “development loans” with interest. The African people bear the repayment, their future mortgaged twice — once by theft, once by debt.

It’s the same triangle, different cargo.

Reclaiming the Narrative

Until African societies confront both sides of their betrayal — the external greed and the internal complicity — the trade continues.

The old slave forts are now museums, but the slave mentality is alive in boardrooms and parliaments across the continent.

Real liberation won’t come from waving flags or electing recycled looters; it will come when Africans refuse to sell their futures for short-term gain, when citizens hold both the thief and his Western banker accountable.

Epilogue

The slave trade never ended; it merely diversified.

Its new product is not the African body but the African dream, exported daily through migration, corruption, and despair.

The only question left is:

How many times must Africa sell itself before it buys back its conscience?