Introduction

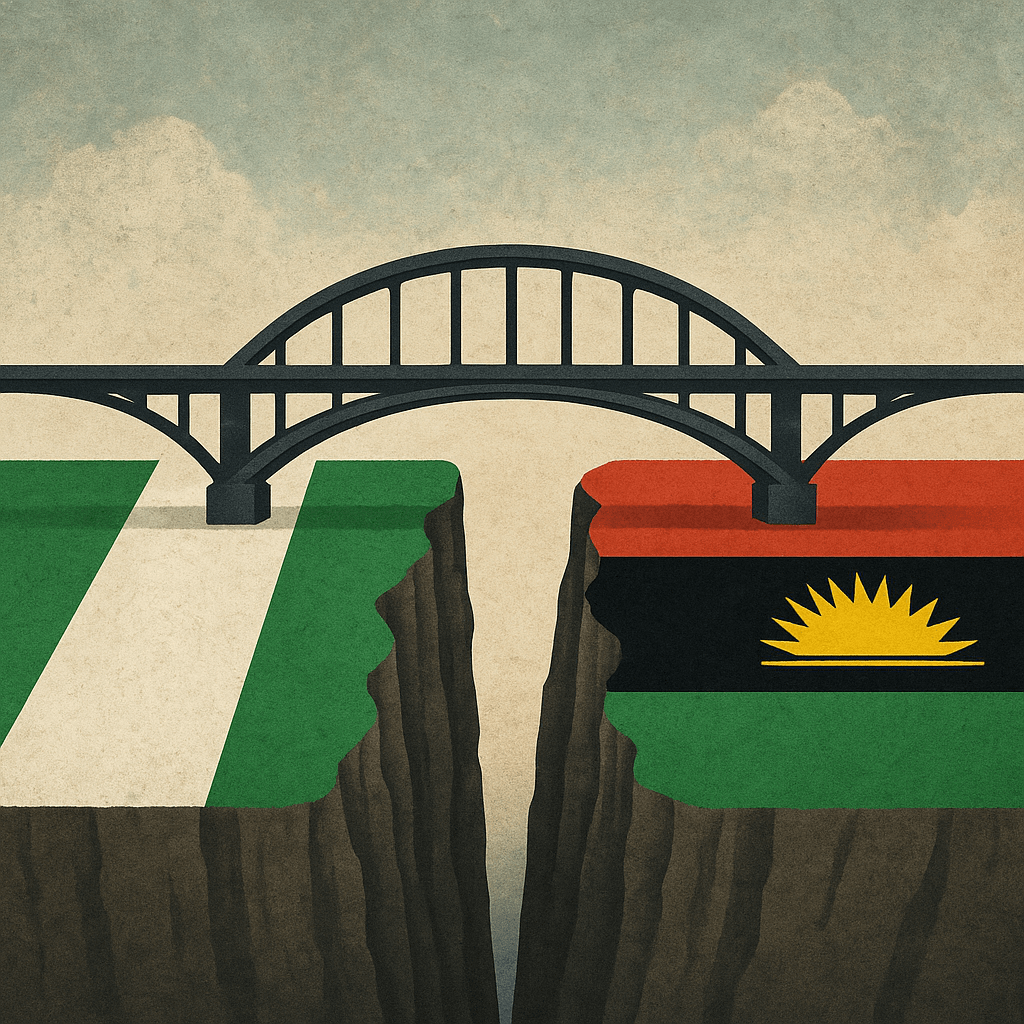

The phrase “No victor, no vanquished” became one of the most enduring political statements in post-war Nigeria. Declared by General Yakubu Gowon in 1970 after the end of the Nigerian Civil War, it was meant to signal reconciliation, forgiveness, and reintegration of the defeated Biafran side into the Nigerian federation. Yet, half a century later, the country remains haunted by the same fault lines of marginalisation, distrust, and uneven justice.

As the Nigerian state grapples with the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) movement and the continued detention of its leader, Nnamdi Kanu, a pressing question arises: can the historical precedents of reconciliation — from Biafra’s post-war settlement, to Niger Delta amnesty, to peace pacts with Northern bandits — provide a viable pathway to resolving the Kanu and IPOB crisis?

The Promise and Failure of “No Victor, No Vanquished”

After three years of brutal conflict, Gowon’s “No victor, no vanquished” declaration offered a symbolic gesture of unity. The policy of “Rehabilitation, Reconstruction and Reintegration” (the 3Rs) aimed to rebuild the East and heal divisions. In practice, however, the policy was unevenly applied. Easterners returning to the national economy faced asset seizures, discriminatory policies, and exclusion from the military and bureaucracy. The scars of war — psychological, political, and economic — remained unhealed.

That unfulfilled reconciliation created a vacuum where grievances fermented. Generations later, the IPOB movement draws from this same well of historical injustice. It frames its struggle not only as self-determination but also as a response to a perceived failure of the Nigerian state to honour the spirit of post-war inclusion.

Niger Delta Amnesty: Buying Peace Through Inclusion

The Niger Delta crisis of the early 2000s presented a different challenge — one rooted in environmental degradation, resource control, and economic neglect. The Yar’Adua administration’s 2009 amnesty deal offered militants pardon, financial incentives, and vocational training in exchange for disarmament.

While imperfect, the policy succeeded in reducing violence and re-integrating many militants into legitimate economic activities. It demonstrated that dialogue and inclusion, not brute force, could pacify militant movements. However, its sustainability depended on continuous engagement and political will — both of which have waned over time.

For IPOB, parallels abound. Like the Niger Delta militants, IPOB operates on deep-seated grievances and a sense of exclusion. But unlike the Niger Delta case, IPOB’s ideology is anchored on identity and sovereignty, not economic compensation. This distinction requires a more nuanced approach beyond cash settlements or political appeasement.

Northern Bandits and the Politics of Selective Reconciliation

The federal government’s recent overtures to armed Northern bandits — including negotiations, amnesty offers, and “repentant terrorist” programmes — expose a troubling double standard. The same state that negotiates with bandits and herdsmen often deploys military might against IPOB.

This inconsistency undermines the moral legitimacy of the state. It communicates that violent agitation in some regions invites negotiation, while peaceful dissent in others invites incarceration. The outcome is a perception that Nigeria practices regional justice — where the ethnicity of an agitator determines whether they are embraced or crushed.

If bandits who terrorised entire communities can be reintegrated through state dialogue, then the continued detention of Nnamdi Kanu, despite court orders, appears both political and discriminatory.

The Kanu and IPOB Question: Towards a Framework for Political Settlement

The IPOB question cannot be solved through suppression alone. The use of proscription, arrests, and extraordinary rendition has hardened positions and polarised the Southeast. The Nigerian government must instead embrace a framework of political negotiation built on three pillars:

Truth and Reconciliation: The federal government must initiate a genuine truth and reconciliation process to address the lingering wounds of the civil war and subsequent marginalisation. This could mirror South Africa’s post-apartheid model, offering acknowledgment and healing rather than denial. Constitutional Dialogue: The IPOB agitation reflects broader discontent with Nigeria’s federal structure. A constitutional conference or restructuring dialogue could address these grievances within a national framework, offering regions more autonomy and control over resources. Amnesty with Accountability: As seen in the Niger Delta case, a well-designed amnesty programme can demobilise agitation if combined with transparent investment in local development and justice. However, it must not become a bribe for silence but a contract for equity.

Conclusion: Reconciling the Spirit of 1970 with the Realities of 2025

The lessons of “No victor, no vanquished” have not been fully realised because Nigeria has confused silence with peace and suppression with stability. The Biafra war ended in 1970, but reconciliation never truly began. The Niger Delta settlement showed that inclusion could calm insurgency; the Northern amnesty to bandits revealed that the state could negotiate with even its fiercest foes.

If the Nigerian government is serious about national unity, it must extend the same reconciliatory spirit to Nnamdi Kanu and the IPOB movement. True peace will not come from victory or vanquish, but from justice — the only foundation upon which reconciliation can stand.