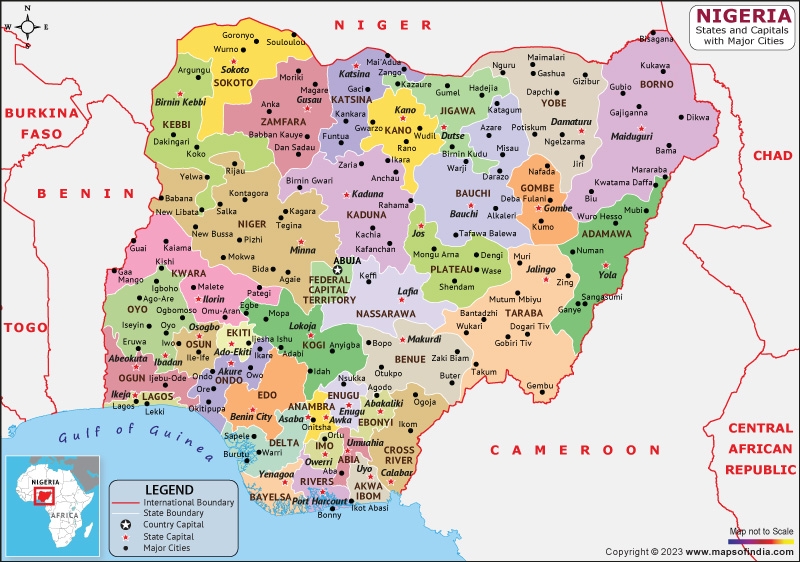

Nigeria’s story is often told in triplicate: the North, the West, and the East. This tripartite division is more than a cultural or political convenience; it is a reality etched into the very landscape by the country’s great rivers. Flowing from the Bight of Benin, the Niger and its major tributary, the Benue, form a vast “Y” shape that naturally carves the nation into three distinct zones. This geographical fact has, in turn, dictated the trajectory of the nation’s political history, with consequences that resonate powerfully today.

From this riverine division emerged the country’s dominant political and ethnic blocs: the Hausa-Fulani in the North, the Yoruba in the West, and the Igbo in the East. Of course, these are broad brushstrokes. Contained within these regions is a vibrant tapestry of minority ethnic and religious groups, each with its own distinct identity. Yet, at the national level, it is the interplay between these three major groups that has defined power dynamics.

A Fractured Independence and the Seeds of Conflict

At independence in 1960, a coalition between the North and the West held the reins of power, with the East largely positioned in opposition. This, too, is a simplistic take, as politics within the West was fractured, with some elements collaborating with the North. This fragile political equilibrium was shattered in January 1966 by a military coup. The coup, which led to the assassination of prominent political leaders from the North and West, was perceived by many as ethnically charged.

The backlash was swift and brutal. By July 1966, a counter-coup led by Northern soldiers erupted, resulting in the death of the country’s first military head of state, General Aguiyi-Ironsi, an Igbo from the East. This was followed by pogroms that targeted Easterners residing in the North. History records that the architects of the counter-coup initially sought to secede and establish a “Republic of Northern Nigeria,” a plan from which they were reportedly dissuaded by British diplomatic pressure. Instead, the ensuing crisis escalated into a full-blown civil war, as the Eastern Region seceded to become the Republic of Biafra. By 1970, the war was over, but the scars remained.

The Long Shadow of Northern Dominance

The post-coup era established a pattern of governance that would define Nigeria for decades. From 1966 onward, with the sole exception of General Olusegun Obasanjo, every military head of state was from the North: Gowon, Mohammed, Buhari, Babangida, Abacha, and Abdulsalami. The brief interlude of civilian rule from 1979 to 1983 was also headed by a Northern politician, Shehu Shagari.

The result is an undeniable statistic: for the majority of Nigeria’s post-independence governance, the highest office has been occupied by Northerners. This prolonged dominance has allowed for the systematic entrenchment of power. Critics argue that national resources have been funneled disproportionately to the benefit of the North.

Today, the evidence of this is seen as institutional. A significant portion of the country’s military assets are located in the North. The national capital was relocated from Lagos in the South to Abuja in the North-Central region. Key infrastructure projects and political appointments are often viewed through this lens of regional favoritism. These structures are, to a large extent, locked into the constitutional framework of the federal system itself, a system which many argue was engineered to perpetuate this advantage.

The Central Fallacy: A Contestable Arithmetic

The justification often given for this power structure is a demographic one: the North, it is claimed, has a larger population and therefore deserves greater political representation and a larger share of national revenue. However, this is a deeply contestable assertion.

Nigeria’s censuses have been historically marred by allegations of politicization and inflation. The idea that the North holds an indisputable demographic majority is a cornerstone of its political hegemony, yet it is a premise that is fiercely challenged by other regions, who point to independent demographic surveys that suggest a very different population distribution.

A Legacy Forged by River and Rule

In conclusion, the rivers that physically divide Nigeria also tell the story of its political fragmentation. The natural boundaries of the Niger and Benue created the stages upon which the nation’s three major ethnic groups have competed for power. The coups of 1966 set in motion a chain of events that led to prolonged Northern dominance, a reality that has been institutionalized within the fabric of the state. The resulting distribution of power and resources continues to be a source of profound tension, underpinned by a demographic argument that remains one of the most contentious and unresolved questions in Nigerian life. The nation continues to grapple with this complex legacy, a testament to how deeply geography can shape destiny.