Introduction: The Clear Blueprint and the Noisy Political Arena

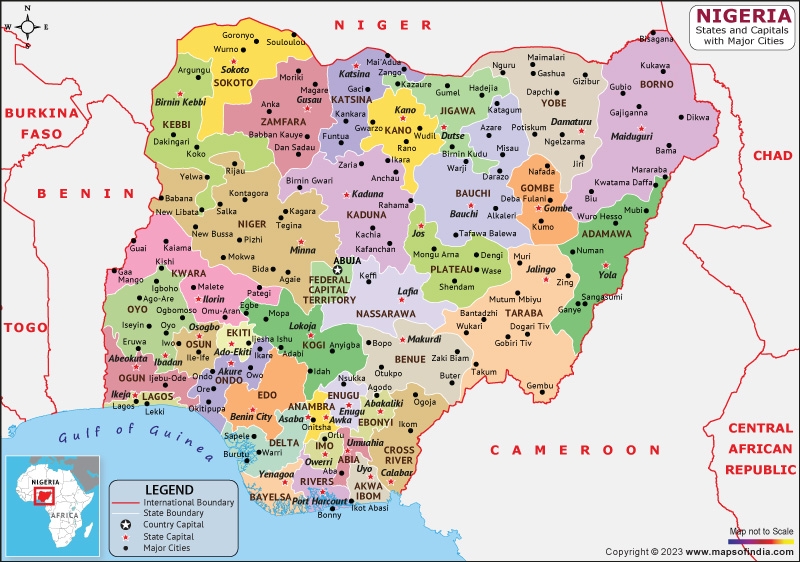

The 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended) stands as the nation’s supreme legal document, providing a detailed blueprint for its governance structure. Within its pages, the procedures for altering the country’s geographical and administrative layout—specifically through the creation of states and local governments—are clearly spelt out in Sections 8 and 3 respectively. These processes are intentionally rigorous, designed to ensure broad consensus and protect the stability of the federation. However, the Nigerian political landscape is rarely a quiet study of legal procedure. Instead, it is frequently animated by vigorous advocacy from politicians, ethnic groups, and regional stakeholders who campaign for new states and local government areas, often creating a public discourse that appears to run parallel to the constitutional framework. The current National Assembly’s consideration of a deluge of proposals for new sub-national entities highlights the persistent and complex tension between the nation’s foundational legal principles and its dynamic political ambitions.

The Constitutional Framework: A Rigorous Path to Creation

The constitution leaves no room for ambiguity regarding the legitimate process for creating new states and local governments. The requirements are multi-layered and demand a high level of political and popular agreement.

The Process of State Creation

According to Section 8(1) of the 1999 Constitution, the journey to a new state is arduous by design:

· A bill must be submitted to the National Assembly. This proposal must be supported by a two-thirds majority of members (Senators and House of Representatives members) representing the area demanding the new state.

· Approval by state and local legislatures. The same proposal must receive a two-thirds majority vote in the state House of Assembly and the local government councils of the affected area.

· A referendum. A referendum of the people within the proposed area must be conducted, and the proposal must be approved by at least a two-thirds majority of voters.

· National and Presidential Assent. The result of the referendum must then be approved by a simple majority of the state Houses of Assembly in at least 24 of Nigeria’s 36 states, followed by the assent of the President.

The Process of Local Government Creation

The creation of Local Government Areas (LGAs) is primarily a state affair, as outlined in Section 8(3) of the constitution:

· A bill for a new LGA must be passed by the State House of Assembly.

· The process requires a request supported by at least two-thirds majority of members representing the area in both the State House of Assembly and the local government councils in the area.

· This must be followed by a referendum approved by a two-thirds majority of the people in the local government area.

· The result of this referendum must then be approved by a simple majority of members in the majority of all local government councils in the state.

· Finally, the result is approved by a resolution passed by a two-thirds majority of the State House of Assembly.

The Reality of Advocacy: Political Agitation vs. Constitutional Procedure

Despite this clear constitutional roadmap, the political arena is often dominated by advocacy that does not neatly follow these legal steps, reflecting deeper socio-political undercurrents.

· Sheer Volume of Proposals: The current National Assembly committee reviewing the constitution is grappling with 55 proposals for new states and 278 for new local governments. This overwhelming number indicates widespread agitation that is channeled into the formal review process, even as the likelihood of any single proposal meeting the strict constitutional tests remains low.

· Historical Context and Military Precedent: It is a historical fact that all 36 existing states in Nigeria were created by military decrees during various military regimes. No civilian administration has successfully created a state since the return to democracy in 1999. This history creates a perception that the democratic process is too slow and difficult, leading some to believe that significant political pressure, rather than strict procedural adherence, is what ultimately leads to success.

· Public Commentary and “Shortcuts”: Public debate often focuses on the outcome—the creation of a new state—while paying less attention to the rigorous steps involved. Politicians may make public promises or traditional rulers may make direct appeals to the president (as seen with the request for Ibadan State), creating a narrative that bypasses the detailed legislative and referendum requirements. This advocacy operates in the court of public opinion, often ahead of the court of law.

· The Challenge of Implementation: Even when the constitution is followed, the final implementation can be a hurdle. For any amendment to be ratified, it must be approved by two-thirds (24) of the 36 state Houses of Assembly. This high threshold has been a stumbling block for several significant reforms in the past, demonstrating that constitutional clarity does not always translate to political consensus.

The Deeper Drivers: Why the Agitation Persists

The relentless push for new states and LGAs, even outside formal channels, is driven by several powerful factors:

· Quest for Equity and Representation: Some regions, notably the Southeast, argue that having only five states compared to other regions’ six puts them at a political and economic disadvantage. This perception of inequity fuels persistent agitation for a sixth state in the region to ensure balanced representation and access to national resources.

· Demand for Local Development and Autonomy: Many communities believe that becoming a state or a new LGA will bring government closer to the people, accelerate local development, and create more opportunities for employment and political representation. They argue that their development is stifled within their current larger administrative units.

· Political Opportunism and Patronage: The creation of new states and LGAs inherently means new governmental structures—new governors, legislators, judges, and civil service apparatus. This represents significant opportunities for political patronage and the expansion of a political class, which can be a powerful motivator for politicians and elites.

Conclusion: Navigating the Delicate Balance

Nigeria’s constitutional provisions for creating states and local governments are a testament to the founders’ desire for a stable, consensus-based federation. They act as a necessary brake on impulsive geographical fragmentation. However, the continuous and vocal advocacy for new entities reflects genuine grievances, historical contexts, and the dynamic nature of Nigerian federalism.

The challenge for the Nigerian polity is to navigate the delicate balance between respecting its supreme law and responding to the legitimate aspirations of its diverse constituents. While the constitution provides the only legitimate path forward, the political advocacy surrounding it is not merely “outside the framework” but is often an attempt to create the momentum needed to navigate that very framework successfully. The true test will be whether this dynamic can be channeled to produce outcomes that are not only constitutional but also equitable and development-focused for the nation as a whole.