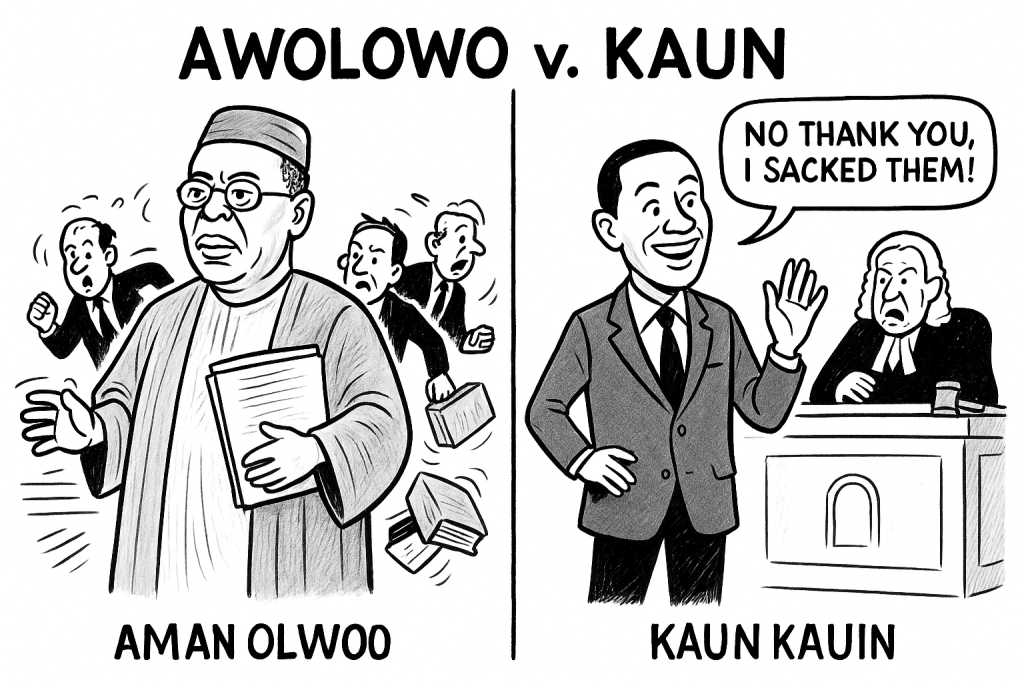

In the annals of Nigerian political-legal theatre, few acts are as eyebrow-raising as a defendant firing his own legal team while standing trial for subversion. And yet, here we are, watching Kaun rewrite procedural audacity for the modern era.

To understand the stakes, one cannot avoid Obafemi Awolowo’s 1962–63 treasonable felony trial. Awolowo, the formidable opposition leader, sought the expertise of a British Queen’s Counsel to defend him against politically charged charges. The Nigerian government, unwilling to tolerate the interference of “foreign wisdom,” refused entry to Awolowo’s chosen counsel. Historians have long viewed this move as legal authority weaponized for political convenience, a subtle nod to the fine line between law and power.

Kaun, however, has flipped the script. Where Awolowo was constrained by the state, Kaun has opted to constrain himself. Sacking one’s own lawyers mid-trial is legally permissible—yes, every defendant has the right to choose their counsel—but doing so in the middle of a subversion trial is like asking a pilot to change copilots mid-flight, then insisting the plane can still land safely.

From a legal standpoint, Kaun’s move is defensible but fraught with peril. Courts will almost certainly ensure procedural fairness, potentially delaying the trial to allow new counsel to familiarize themselves with the case. But fairness does not equal wisdom; a self-imposed handicap rarely bodes well for strategic outcomes.

Historically, this act reads like a reversal of the Awolowo precedent. Whereas the First Republic’s machinery refused the defendant access to his lawyer, Kaun has voluntarily cut off his line to legal expertise. Scholars will likely note this as an unusual maneuver, one that risks undermining the trial while simultaneously serving as a bold political statement: a gesture of defiance, a distrust of the system, or perhaps a stunt for the historical record.

Public perception, of course, is a different battlefield. Supporters may hail it as a principled act of self-determination, while detractors will see reckless self-sabotage. Either way, Kaun has ensured his trial will be studied, not just for the charges, but for the curious choreography of his defense—or lack thereof.

In short, Kaun has written himself into history as the man who fired his own lawyers in a subversion trial, a move both legally permissible and historically fascinating. Awolowo’s case reminds us that governments can constrain defendants; Kaun reminds us that sometimes, defendants constrain themselves—with dramatic flair.

And in the annals of Nigerian political-legal drama, flair has its own peculiar currency.