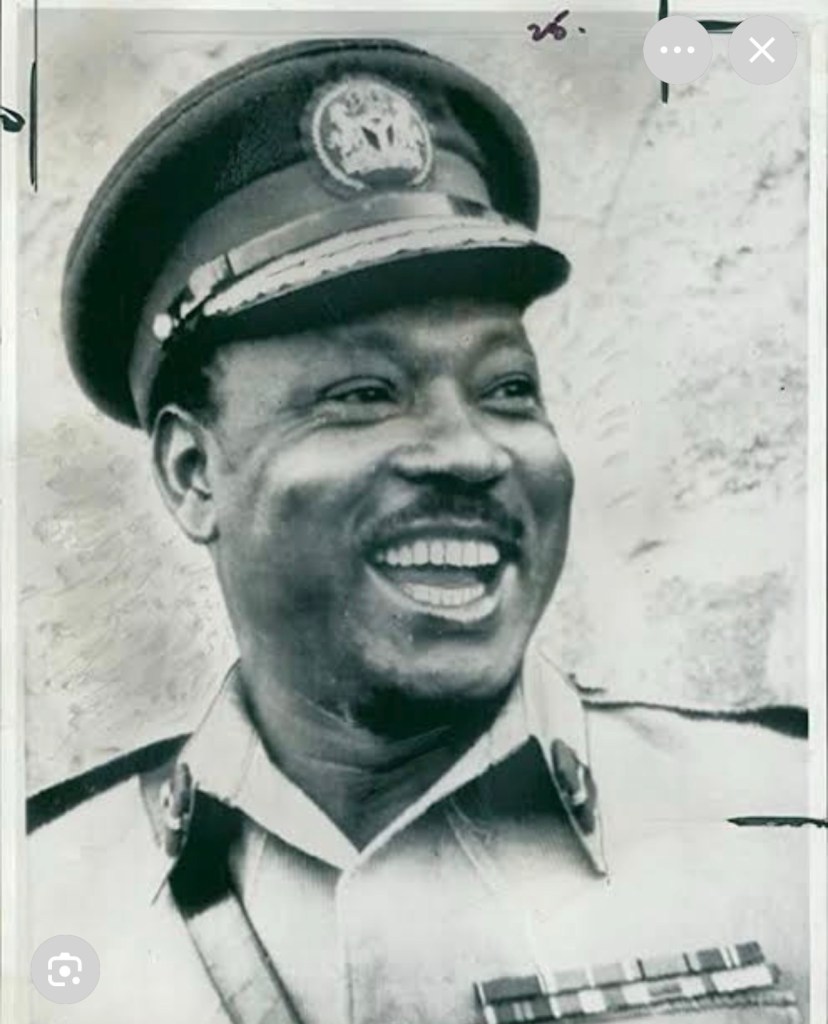

The creation of states in Nigeria is often discussed as a necessary restructuring of the old regional system, a move to dismantle centrifugal forces and foster national unity. At the heart of this foundational shift lies Unification Decree No. 34 of May 24, 1966, promulgated by the military government of General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi. The decree abolished the federal structure and established a unitary “Republic of Nigeria.” While it was officially rescinded mere months later following Ironsi’s assassination, a critical examination reveals a provocative truth: the decree’s spirit did not die; it was merely re-clothed. It became the de facto operating system for all subsequent military regimes and, arguably, continues to shape the backdrop of Nigeria’s constitutional practice even under civilian rule.

The Decree and Its Stated Alternative

Decree No. 34 was a radical, top-down solution to the profound regionalism and ethnic tensions that culminated in the 1966 coup and counter-coup. Ironsi’s government, having seized power, faced a crisis of legitimacy and cohesion. The decree’s rationale was “unification” – to break the power of the regions and centralise authority in a bid to forge a singular Nigerian identity.

But was there an alternative? Unequivocally, yes. The alternative was not necessarily a return to the status quo ante, but a reformed, rebalanced federation. Instead of outright abolition, a military government possessing coercive power could have used its authority to recentralise specific, critical functions (like security and resource allocation) while retaining the framework of federating units. It could have created a stronger central government within a federal constitution, as was later attempted in 1979. The choice to impose a unitary state was not an inevitable outcome of military rule; it was a specific ideological and political decision that reflected the Ironsi regime’s diagnosis of Nigeria’s ailment. The violent backlash from the Northern region, which saw the decree as a tool of Southern domination, proved its political impossibility in its explicit form.

The Decree in Spirit: The Enduring Military Ethos

Although General Yakubu Gowon restored the word “federation” and created 12 states, the operational ethos of Decree No. 34 remained fully intact throughout the 29 years of military governance. The military’s command-and-control structure is inherently unitary and hierarchical. As the head of state, the military president commanded the entire apparatus of the state. The governors of the newly created states were not elected representatives nor administrative heads of federating units; they were military officers on assignment, directly appointed by and reporting to the Supreme Headquarters.

This system perpetuated the “ethos” of Decree No. 34 in practice:

- Centralised Command: All directives flowed from the centre. State governors implemented federal policies without meaningful local legislative input.

- Absence of Federal Bargaining: The concept of federating units bargaining with the centre was null. The “federation” was administered as a chain of command.

- Resource Control from the Centre: The centralisation of revenue allocation, cemented by the Armed Forces Decree No. 13 of 1970, mirrored the unitary economic control envisioned by Decree No. 34.

Thus, while the map was redrawn to look federal, the governance was unmistakably unitary in spirit—a direct perpetuation of Ironsi’s original blueprint, now executed under the less provocative label of a “federation.”

The Civilian Inheritance: A Constitutional Backdrop

The return to civilian rule in 1999 did not constitute a clean break from this deeply ingrained system. The “bare essential” of Decree No. 34—a powerfully centralised federal government—remains the dominant backdrop of the 1999 Constitution. The document, itself a product of a military transition, tilts overwhelmingly towards the centre.

Evidence of this enduring spirit is manifest:

· The Exclusive Legislative List: Containing 68 items, it grants the federal government overwhelming control over key economic and security sectors, leaving states with limited autonomy.

· Control of Resources: The federal government retains primary control over mineral resources (most critically, oil and gas), a centralising feature born in the military era.

· The “Federal Character” Principle: While designed for equity, its application often reinforces the centrality of federal appointments and patronage.

· Weak Subnational Fiscal Autonomy: States remain heavily dependent on monthly allocations from the Federation Account, replicating the dependency of military-era governors on the Supreme Headquarters.

In essence, Nigeria’s civilian federation operates on a constitutional template forged in the furnace of military unitarism. The political bargaining and compromise typical of organic federations are stifled by a structure designed for hierarchical control.

Conclusion

Unification Decree No. 34 was not an isolated, short-lived edict. It was the seminal expression of a centralising impulse that became the default setting for military governance in Nigeria. The alternative of a genuinely devolved federation was available in theory but was consistently rejected in practice by a succession of military regimes that found the command model more expedient. Today, Nigeria’s democracy grapples with the legacy of this choice. The relentless calls for “restructuring,” true fiscal federalism, and state police are, in fact, appeals to finally exorcise the enduring spirit of Decree No. 34 and build a federation that derives its strength not from imposed unity, but from the cooperative consent of its truly empowered parts. The ghost of May 24, 1966, still walks the corridors of power in Abuja.