On a humid Lagos morning—because Lagos refuses to ever be cool—soldiers with fixed bayonets were busy shooing away a crowd of small boys outside the federal parliament. “Go ‘way, go ‘way! No children today!” they shouted, as if the country was merely expecting an unpleasant visitor, not a complete regime change.

Across town at the Ikoyi Hotel, scrubwomen were scrubbing bloodstains off the marble with Dettol, the national disinfectant of both wounds and scandals. To complete the eerie atmosphere, telephones mysteriously stopped working—as they do anytime trouble wants peace and quiet. And the government radio station cleared its programs, filled the airwaves with random music, 15 minutes of talking drums, a recycled travelogue, and an overplayed sermon whose needle got stuck repeating:

“Charity envieth not… charity envieth not… charity envieth not…”

Clearly, even the record was foreshadowing trouble.

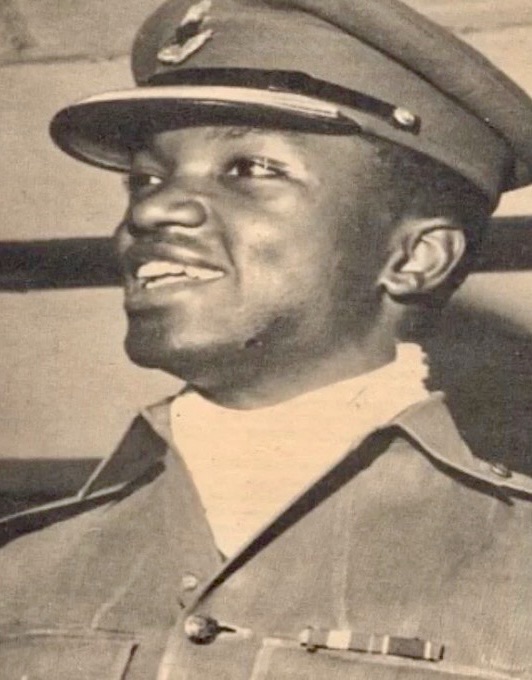

Then came the announcement every Nigerian had been waiting for: a jubilant military voice declared, “I, J.T.U. Aguiyi-Ironsi, have been invested with authority as Head of the Armed Forces.” In one breath, the Major General—known as “Johnny Ironsides”—tossed the constitution aside, dissolved the offices of President and Prime Minister, dismissed the regional premiers, and installed military governors. Democracy did not just die; it died suddenly, without even leaving a forwarding address.

The Night of Sandhurst Thunder

The coup itself was a meticulous demolition job. Five young Sandhurst-trained officers—graduates of the British “How to Run a Proper Coup” academy—neutralized their seniors and seized major military units. In coordinated strikes, they assassinated or abducted the Sardauna of Sokoto, Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh, Chief Samuel Akintola, and Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa. Nigeria’s political class had been dramatically unplugged.

Residents recalled the efficiency:

“Sandhurst training certainly leaves its mark,” one Englishman muttered, likely clutching his tea.

In Kaduna, Major Chukwuma Nzeogwu had rehearsed for weeks, holding night maneuvers so frequently that gunfire became background noise. So when he finally attacked the Sardauna’s palace, even the police didn’t bother investigating. A grenade, a firefight, and a tragic execution later, northern Nigeria had lost its most powerful political figure.

Meanwhile in Ibadan, Akintola met a similar fate. Lagos too was busy: the Prime Minister submitted calmly, hands raised; Okotie-Eboh tried to bribe the soldiers with “dash,” then fled screaming into the night in pajamas. Neither lived to see the next sunrise.

By week’s end, more bodies surfaced—including on the 13th tee of the Lagos golf course. Nigeria had just witnessed the bloodiest coup in black African history.

A Country Built Like a Patchwork Quilt… and Fraying

Nigeria’s deep fractures didn’t begin that night. With 250 tribes and 250 languages, the country was always a colonial puzzle held together by prayer, hope, and census manipulation.

The North—larger and predominantly Muslim—dominated early politics. The South resented it. The result: anarchy by appointment.

Corruption flourished.

Ministers became businessmen; businessmen became ministers; everyone became a landlord. Okotie-Eboh’s “dash” economy thrived, and his shoe factory enjoyed protective tariffs because—well—he wrote them.

In the Western Region, politicians collected salaries like they were Pokémon: gotta catch all 54 ministerial positions! President Azikiwe, conveniently recuperating in England, had once called it “a world record”—and he wasn’t praising them.

Elections were rigged like poorly concealed magic tricks. Census figures suspiciously favored the North. Opponents were jailed. By late 1965, Western Nigeria descended into violence; cars were stopped by political gunmen demanding “contributions,” and truck drivers demanded hazard pay to simply stay alive.

When the Sardauna and Akintola secretly agreed to call in the army to crush the chaos, the junior officers—already fed up—said, “Not today.” And the coup began.

Nzeogwu summed up their motivation:

“Our enemies are the political profiteers, the bribe-seekers, the tribalists, and nepotists who have corrupted our society.”

Ironsi Steps In: From Revolution to Reset

The coup plotters expected to rule, Nasser-style. But they underestimated Johnny Ironsides. As senior officers regained control, Ironsi took charge, appointed moderate military governors, recalled Nzeogwu, and promised a constitutional reset.

His message to the nation was simple: “We’re here to maintain law and order.”

(Translation: “Relax, we are not here to stay forever… I think.”)

Nigerians, exhausted from chaos, welcomed him like a relief package. Students paraded a coffin labeled “Tyranny Has Died.” Unions cheered. Even the dethroned Northern People’s Congress saluted the new order.

The West African Pilot declared, “Independence is finally won!”

That was optimistic, but Nigerians love hope the way Brits love tea.

The Unfinished Story

Yet beneath the southern jubilation, the North simmered. Any new constitution would likely break up the vast northern region—ending a political advantage it had enjoyed since independence. And the assassination of the Sardauna stirred fears of a religious or regional backlash.

The coup ended one power struggle but opened the door to another—this time within the army itself.

Nigeria thought democracy had taken a break. It didn’t know the break would last much longer… and come with sequels.