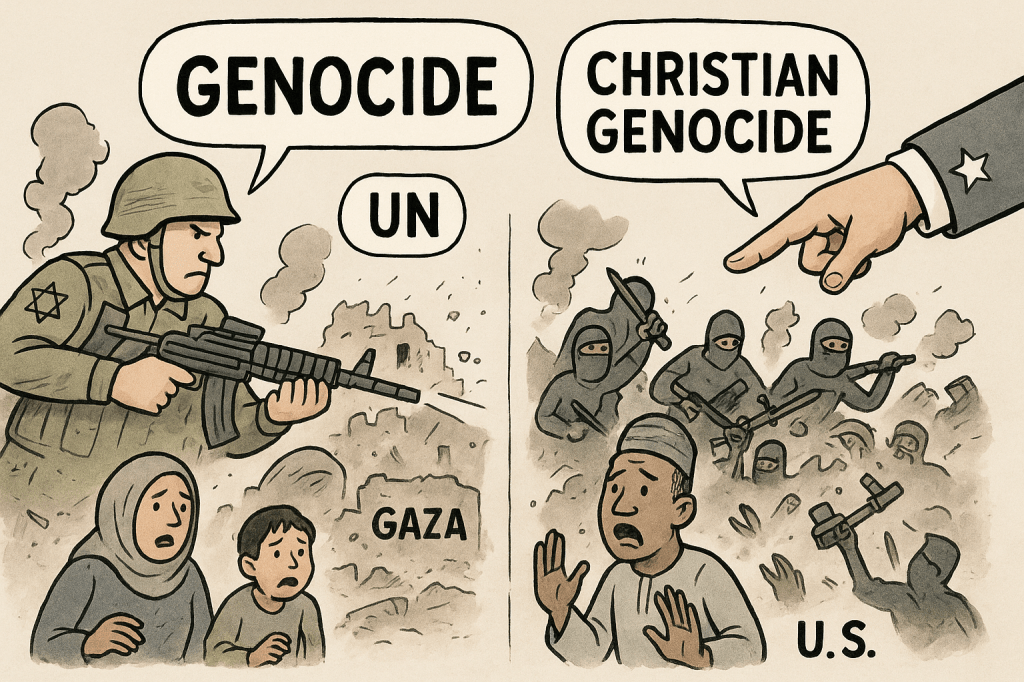

In the brutal arithmetic of global politics, the word genocide is not merely a legal definition—it’s a geopolitical weapon. Its deployment, timing, and emotional force often reveal more about international alignments than about the actual facts on the ground. Nowhere is this clearer than in the contrasting treatment of Israel’s war in Gaza and the episodic violence within Nigeria.

Israel, Gaza, and the Charge Heard Around the World

Israel, a state with overwhelming military dominance, unleashed the full spectrum of its armed forces on Gaza. This is a defined strip of land, bounded, isolated, and heavily documented. Statements by Israeli actors regarding intent were widely circulated. The consequences—cities flattened, civilian populations decimated, infrastructure erased—were visible in real time.

A significant majority of UN member states, respected international legal bodies, and human rights institutions concluded that the scale, pattern, and rhetoric surrounding the operation met the legal threshold for genocide—or at minimum demanded genocide investigations. Crucially, the United States, the world’s lone superpower, provided Israel not only with weapons, but a diplomatic shield and legal insulation.

Religious identity, geographic containment, expressed intent, and sheer scale combined to make Gaza one of the most legally and politically clear-cut accusations of genocide in the 21st century.

Nigeria: A Different Reality, A Different Logic

Contrast this with Nigeria.

Nigeria’s security breakdown is real, catastrophic, and unacceptable—but its character is fundamentally different. The violence is perpetrated by non-state actors: bandits, terrorists, separatist militias, criminal groups. They kill Christians and Muslims alike. They attack farms, highways, villages, and city outskirts indiscriminately.

No credible evidence has ever surfaced to suggest that the Nigerian state—under any administration—is orchestrating or supporting the killing of Christians, Muslims, or any group. There is no state policy of extermination. No official rhetoric of elimination. No identifiable state machinery pursuing an ethnic or religious group.

Yet, in the judgment of the United States, Nigeria suddenly became a “country of particular concern”—a label typically reserved for states with active government-sponsored religious persecution. No UN report, no international tribunal, no regional human rights body, and no reputable global watchdog has declared Nigeria guilty of genocide or genocidal intent.

The puzzle is clear: how did Nigeria get thrown into the same basket?

Rwanda: The Legal Gold Standard of Genocide

If one seeks clarity, go to Rwanda. There, the definition of genocide is not theoretical—it is historical fact.

A majority ethnic group, the Hutus, supported by state apparatus, media, and military institutions, moved systematically to eliminate the Tutsi population. More than one million people were slaughtered in 100 days. Local courts, international tribunals, and global diplomacy all converged on the same conclusion: this was genocide beyond doubt, beyond politics, beyond spin.

This is the benchmark against which claims of genocide are measured. Nigeria, with its chaotic, decentralised violence, simply does not fit this mould.

The Politics Behind Nigeria’s Sudden “Genocide Spotlight”

The allegations of a Christian genocide in Nigeria did not arise organically from facts on the ground. They surfaced at the peak of global outrage at Israel’s actions in Gaza—precisely when more countries began recognising Palestine and challenging the US-Israeli narrative.

At that moment, pro-Israel groups and conservative political blocs sought a counter-argument:

If Christians are being exterminated in Nigeria, why is the world focused only on Gaza?

It was a diversionary tactic—an attempt to create moral equivalence where none existed.

The Trump administration, already operating with a foreign policy driven by evangelical politics and transactional alliances, amplified the claim dramatically. It escalated the rhetoric, threatened sanctions, and even hinted at military intervention—all without any serious, verifiable evidence.

In short, Nigeria became a pawn in a much larger geopolitical chess match, dragged into a debate where the facts were secondary to the optics.

Conclusion: Facts Matter, Even When Geopolitics Doesn’t Want Them To

Nigeria’s security collapse is real, tragic, and demands urgent structural reform. But it is not genocide, and no international legal authority says it is. Israel’s war in Gaza, by contrast, sits under the weight of global legal opinion and the documented reality of state-driven, overwhelming, and targeted destruction.

Yet, in the theatre of global politics, facts often bow to strategy. Nigeria’s name was invoked not because the world cared about Nigerians, but because someone cared about winning a geopolitical argument elsewhere.

And that, perhaps, is the real tragedy: when genocide becomes a political instrument, truth becomes collateral damage.