In most countries, a godfather is a benevolent figure who buys you ice cream, attends your graduation, and disappears quietly into family WhatsApp groups. In Nigeria, however, a godfather is a political institution—he buys you an election, attends your swearing-in, and then moves permanently into Government House. Rent-free. In your head.

Godfatherism, Nigeria’s most enduring export after crude oil and broken promises, is the political system where democracy exists—just with supervision. It is the arrangement by which powerful men (and they are almost always men) sponsor elections the way venture capitalists sponsor startups: heavy investment upfront, aggressive control, and ruthless liquidation if returns are delayed.

Welcome to Nigeria’s peculiar version of democracy: government of the people, by the godfather, for the godfather.

How It Works (Or How You Don’t)

The process is simple. A godfather identifies a promising godson—usually loyal, pliable, and financially exhausted. The godfather then deploys his assets: money, party structures, security agencies, thugs with matching uniforms, and sometimes prophets who have suddenly received divine insight about election outcomes.

The godson wins. Democracy rejoices. Ballot boxes smile.

Then the bill arrives.

Because godfatherism is not charity; it is a hire-purchase agreement. The godson must repay through contracts, appointments, budget lines, immunity from prosecution, and the occasional public declaration of eternal gratitude. Independence is not included in the package. That’s a premium feature.

If the godson develops dangerous ideas—like “governing” or “thinking independently”—the godfather reacts the way any investor would: hostile takeover. Cue impeachment threats, court injunctions issued at 2 a.m., burning of legislative chambers, or sudden rediscovery of corruption allegations that were mysteriously invisible during campaigns.

Monetised Democracy: Now Selling Governance by the Billion

In Nigeria, elections are no longer contests of ideas; they are auctions. Politics has been fully monetised. You don’t run for office—you are installed, like a DSTV decoder.

Billions of naira are poured into elections, instantly excluding teachers, professionals, or anyone without a billionaire sponsor or a successful kidnapping résumé. Public office becomes a profit centre, and governance is reduced to revenue recovery.

This is why campaign promises sound like motivational quotes rather than policy plans. Nobody expects delivery; everyone expects returns.

Violence: The Godfather’s Customer Service Department

To enforce compliance, many godfathers maintain “youth wings,” “stakeholders,” or “political structures”—known elsewhere as militias, thugs, cult groups, and people who disappear after elections but reappear during crises.

They intimidate voters, chase opponents, and sometimes chase governors themselves. In extreme cases, democracy is escorted at gunpoint. Peaceful transfer of power is encouraged—but violence is always on standby, just in case peace misbehaves.

A Brief History of Big Men Doing Big Things

Godfatherism didn’t start yesterday. Nigeria has always loved patrons. In pre-colonial times, it was chiefs. During colonial rule, it was elite brokers. After independence, towering figures like Ahmadu Bello, Obafemi Awolowo, and Nnamdi Azikiwe shaped politics from behind the scenes—though with ideology, structure, and at least a pretence of nation-building.

Then came the Fourth Republic in 1999, oil money, weak institutions, and the realisation that democracy could be privatised. Godfatherism didn’t just return; it scaled.

Hall of Fame (Or Shame)

No discussion of Nigerian godfatherism is complete without its legends.

Bola Ahmed Tinubu (Lagos) is widely regarded as the Cristiano Ronaldo of godfatherism: disciplined, strategic, and serially successful. From 1999 to date, Lagos politics has operated like a well-run franchise. Governors come and go, but the brand remains. Those who forget who owns the trademark—ask Akinwunmi Ambode—are quickly reminded.

Chris Uba (Anambra) provided the industry’s most criminal tutorial. After installing Chris Ngige in 2003 and being politely ignored, Uba responded by kidnapping the sitting governor at gunpoint. Democracy survived, barely. Nollywood took notes.

Lamidi Adedibu (Oyo), the strongman of Ibadan politics, sponsored Rashidi Ladoja and then attempted to govern Oyo State from his living room. When Ladoja resisted, impeachment followed. Street violence ensured democracy understood its place.

James Ibori (Delta) allegedly turned state power into an international career, later completed abroad with a money-laundering conviction. A reminder that Nigerian godfatherism is globally competitive.

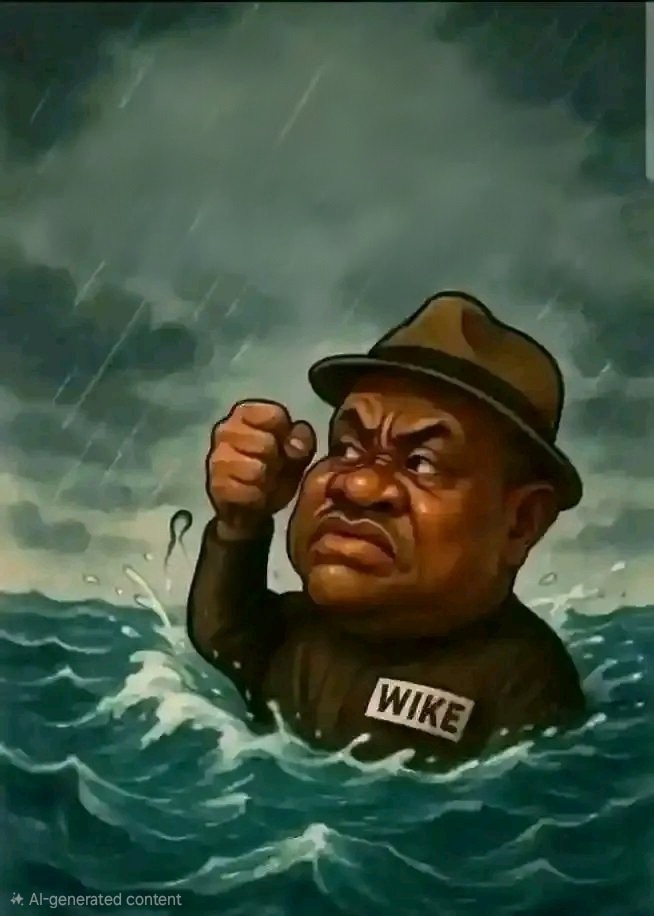

And now, the season finale: Nyesom Wike vs. Siminalayi Fubara (Rivers). Wike installed Fubara. Fubara discovered free will. Rivers State promptly descended into legislative arson, impeachment threats, defections, and political theatre so intense even Shakespeare would demand royalties. As of 2026, governance is on hold while godfather and godson argue over who owns the remote control.

Democracy, Nigerian Style: Side Effects May Include Paralysis

The consequences are predictable. Meritocracy is replaced with loyalty tests. State resources are diverted to settle political debts. Governance stalls as budgets become battlefields. Violence becomes normalised. Citizens, exhausted, begin to see democracy not as people power but as elite entertainment.

Voters are reduced to spectators, watching billionaires fight over mandates they did not earn.

Is Godfatherism Finally Dying?

Some optimists point to recent rebellions—governors defecting parties, aligning with presidents, or attempting escape velocity from their political creators. This is less the end of godfatherism and more internal restructuring. The godfather model is weakening in places, but it remains dominant—especially where oil money flows and institutions leak.

The system will persist until elections are cheaper, parties are democratic, institutions are independent, and citizens stop worshipping “strong men” who cannot build strong systems.

Until then, Nigeria’s democracy will continue to come with a disclaimer:

This government may be controlled by unseen hands. Side effects include impeachment, violence, budget crises, and sudden midnight court orders. Consult your godfather before making policy decisions.