The Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970), also known as the Biafran War, stands as one of Africa’s most devastating post-colonial conflicts. As millions faced starvation, a complex web of international diplomacy and military supply fueled a conflict that political negotiations seemed powerless to stop. This article explores the doomed peace talks—from Ghana to Ethiopia—and reveals how foreign powers, from London to Moscow, prolonged the suffering by prioritizing geopolitics over peace.

The story of failed diplomacy begins not in the midst of war, but in a last-ditch effort to prevent it. In January 1967, key military leaders from Nigeria’s regions met in Aburi, Ghana. The atmosphere was surprisingly cordial, and a significant agreement was reached. The Aburi Accord proposed a confederal Nigeria, decentralizing power to the regions and requiring unanimous agreement in the Supreme Military Council for major national decisions.

The Aburi Accord: The Last Chance for Peace

For a moment, peace seemed possible. However, this hope was short-lived. Upon returning to Lagos, the Federal Military Government under General Yakubu Gowon issued Decree No. 8, which reinterpreted the accord to grant the federal government emergency powers to intervene in the regions. The Eastern Region’s leader, Lieutenant Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, viewed this as a profound betrayal of trust. The complete breakdown over implementing the Aburi Accord is widely seen as the direct catalyst for the Eastern Region’s declaration of independence as the Republic of Biafra on May 30, 1967, plunging the nation into a 30-month civil war.

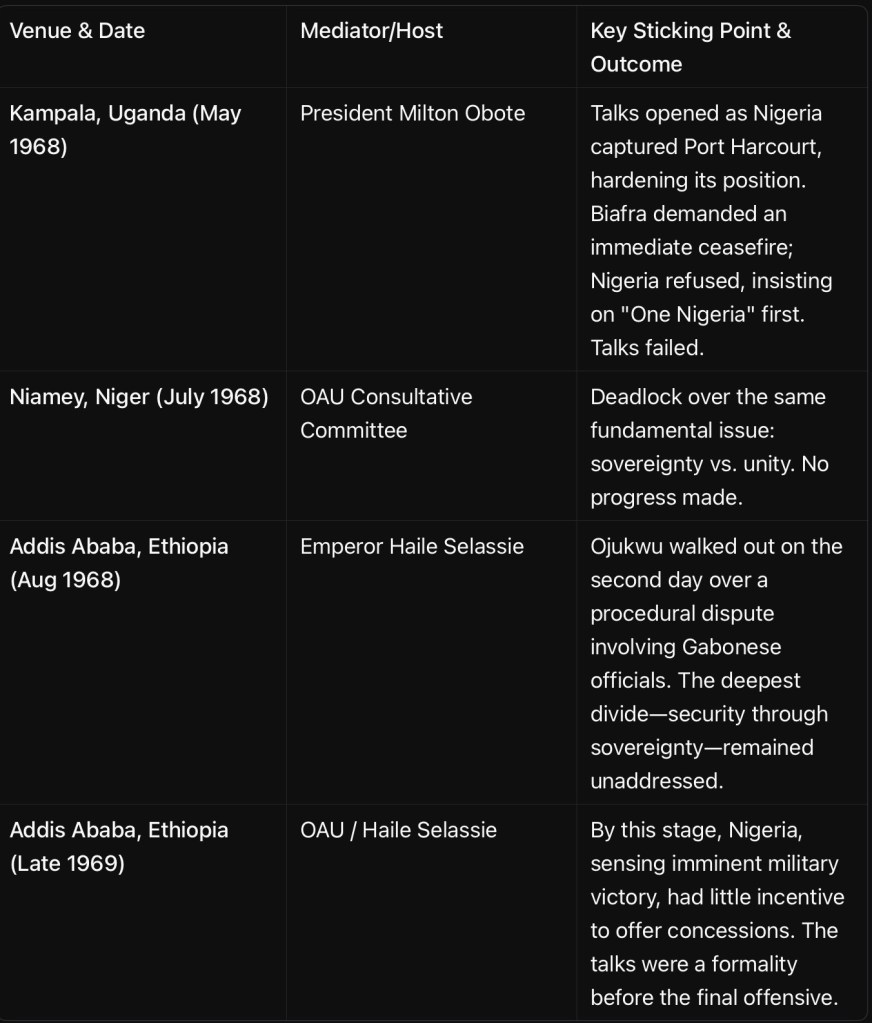

A Diplomatic Tour of Failure

Once the war began, the international community, led by the Organization of African Unity (OAU), launched a series of peace initiatives. Each followed a painfully predictable pattern of collapse, trapped between two non-negotiable positions.

The Core Irreconcilable Demands

· Nigeria’s Stance: “One Nigeria” was an unshakable principle. Any discussion had to begin with Biafra renouncing secession and accepting the nation’s territorial integrity. For the federal government, this was a fight against rebellion, not a negotiation between sovereign states.

· Biafra’s Stance: Sovereignty was non-negotiable for survival. Ojukwu argued that the pogroms against Igbo people in 1966 and the federal betrayal of the Aburi Accord made life within Nigeria impossible. Biafra demanded recognition as a precondition for any substantive talks.

Chronology of Collapsed Talks

A tragic subplot to the Kampala talks underscored the war’s brutality: the mysterious kidnapping and murder of Johnson Banjo, a Nigerian civil servant serving as a secretary to the delegation. His unsolved death cast a long shadow over the proceedings.

Were the Talks Ever Serious?

It is an oversimplification to claim that participants never took the talks seriously. For Biafra, diplomacy was a crucial weapon—its primary tool for gaining international recognition, humanitarian sympathy, and putting pressure on Nigeria. For Nigeria, participation was a strategic necessity to legitimize its position as the lawful government responding to rebellion and to appease international calls for peace.

However, both sides undeniably used negotiations as an extension of the battlefield. Talks served as opportunities for propaganda, to buy critical time for military resupply and reorganization, and to demonstrate “reasonableness” to foreign observers. The fundamental lack of willingness to compromise on core existential goals—preserving the state versus creating a new one—meant diplomacy was doomed from the start. As a 1969 U.S. State Department memo astutely noted, the dynamics of the battlefield directly poisoned the negotiating table: any circumstance that might force Biafra to make concessions would simultaneously make a victorious Nigeria less willing to offer any.

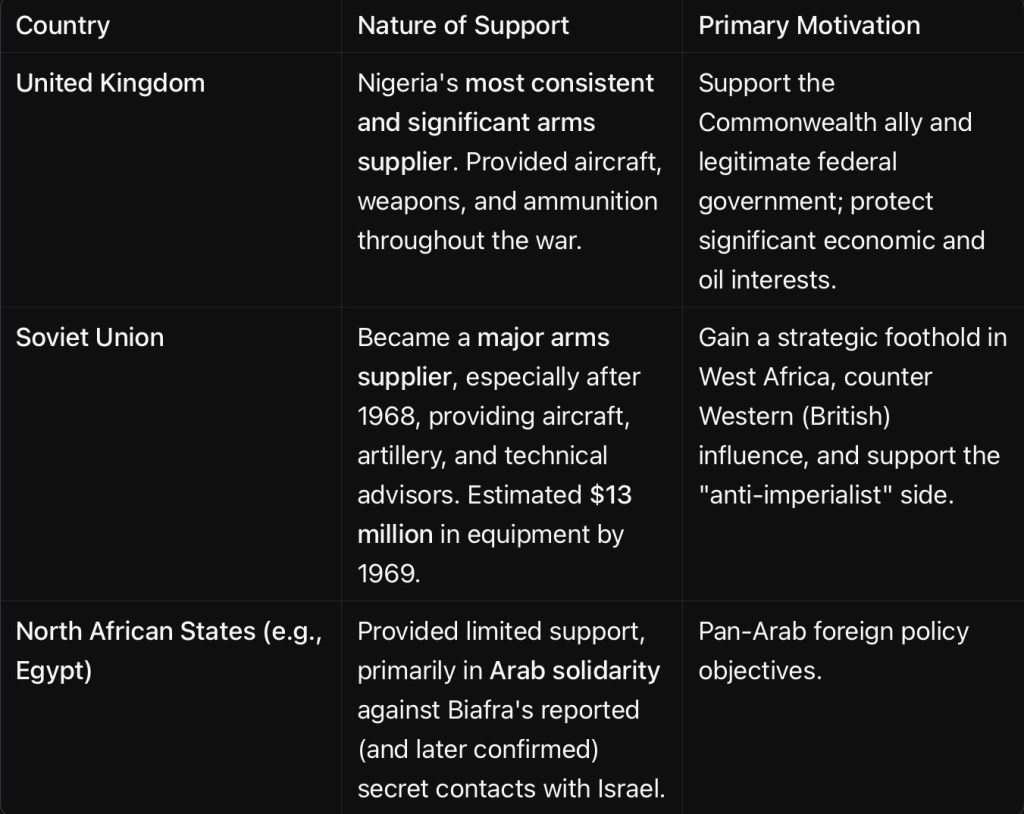

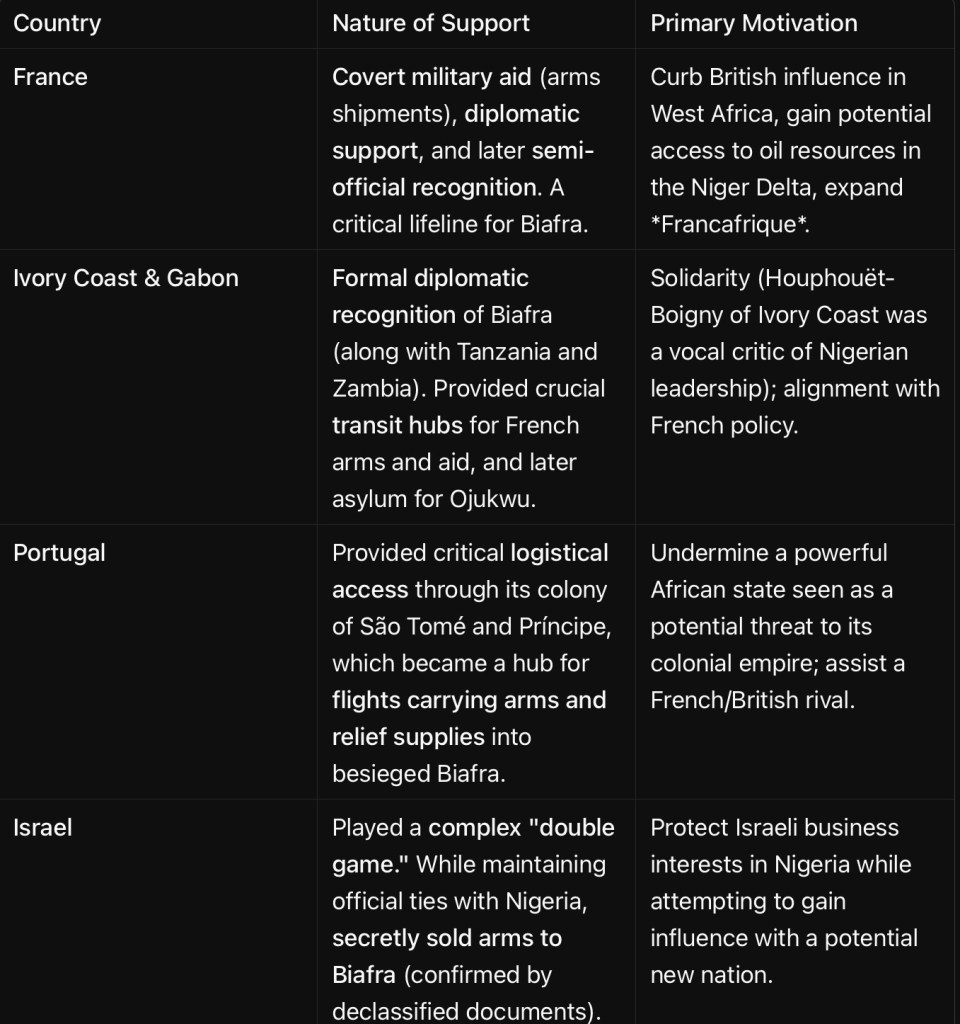

The Foreign Fuel: How International Arms Prolonged the War

If the peace talks were a feeble flame, foreign military assistance was the wind that fanned the war into a protracted conflagration. The conflict became a proxy arena where Cold War and post-colonial rivalries played out, with devastating consequences for civilians.

The Backers of Nigeria

The Backers of Biafra

This external military support created a devastating equilibrium. British and Soviet supplies ensured Nigeria could maintain its strategic blockade and sustain offensives. French and covert channels ensured Biafra could survive, resist, and prolong the war. Each shipment of weapons made the possibility of a negotiated settlement more remote, as both sides held out hope for a military solution enabled by their foreign patrons.

The Fatal Intersection: Diplomacy Meets the Arsenal

The peace talks and the arms pipelines were not separate stories; they were intimately connected in their failure. The Kampala talks in May 1968 collapsed just as Nigeria, buoyed by fresh supplies, captured the strategic port city of Port Harcourt, eliminating any incentive for compromise. The Addis Ababa talks in late 1969 were rendered meaningless because Nigeria’s military, armed with Soviet jets and British artillery, was on the cusp of a final victory.

Western governments, particularly Britain, found themselves in a morally untenable position: championing peace talks while simultaneously supplying the weapons that made peace impossible. Internal U.S. government analyses from 1969 concluded that a successful American mediation would be seen as a “substantial failure of policy” for British Prime Minister Harold Wilson, highlighting how entrenched national interests overrode humanitarian diplomacy.

Conclusion: The Legacy of a War Won by Arms

The Nigerian Civil War ended on January 15, 1970, not with a peace treaty signed at a negotiating table, but with a military surrender on the battlefield. The Federal Government’s noble post-war policy of “No victor, no vanquished” aimed at reconciliation, but it could not heal all wounds. The underlying issues of federalism, resource control, and ethnic identity that caused the war were left largely unresolved, a legacy that continues to shape Nigerian politics today.

The story of the Biafran peace talks is a sobering lesson in the limits of diplomacy when it is not backed by a genuine will for compromise and when it is actively undermined by the flow of foreign weapons. It remains a poignant case study of how geopolitical gamesmanship can prolong human suffering, ensuring that the path of war remains open long after the doors of dialogue have been closed.