There are moments when television does more than entertain. It pauses mid-monologue, clears its throat, and quietly hands policymakers a solution—only for them to ignore it and borrow more money instead.

One such moment came in The West Wing, season 7, during a fictional presidential debate that now feels uncomfortably like a policy memo Nigeria never opened.

The Scene: Hollywood, Idealism, and an Uncomfortable Truth

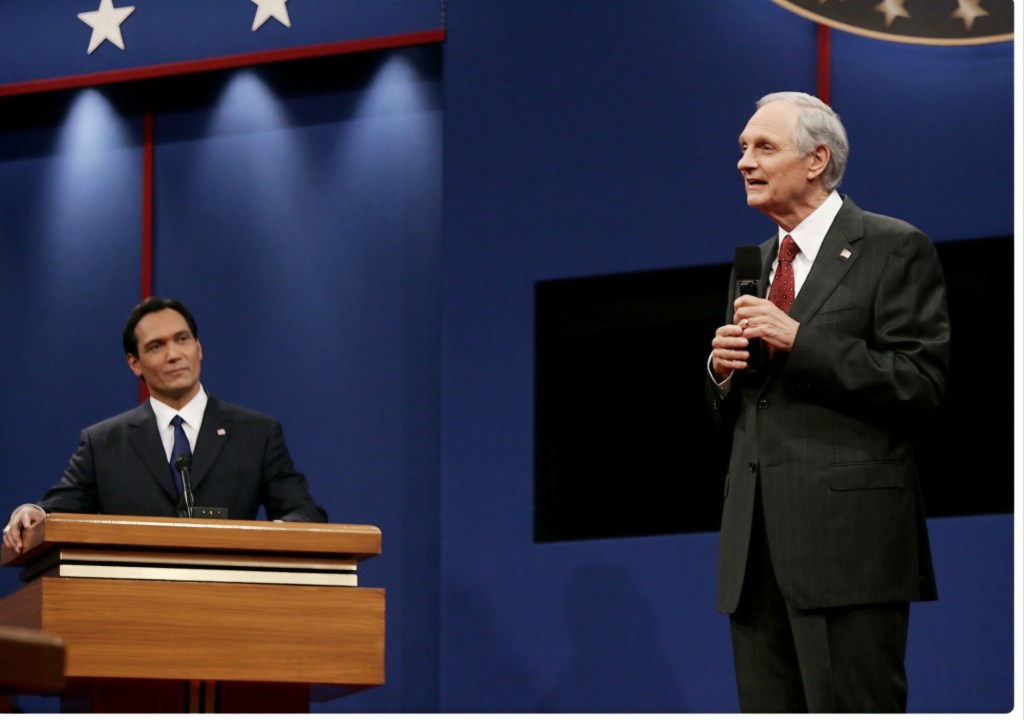

In the debate, Senator Arnold Vinick (played with infuriating calm by Alan Alda) is asked how to deal with persistent poverty and suffering in African countries. The question sounds familiar. The answers we usually hear are also familiar: aid, debt relief, more conferences in air-conditioned hotels.

Vinick does something radical. He talks about taxes.

Not corruption.

Not charity.

Not “capacity building.”

Taxes.

He argues that in many African economies, tax policy itself is the poverty trap.

Vinick’s Heresy: Too Much Tax, Too Soon

Vinick points to countries where income tax rates kick in at laughably low income levels, combined with broad VAT regimes that touch almost everything that moves. In his example—Tanzania—workers face a 30% income tax at levels that, in richer countries, might barely qualify you for a bus pass.

To Vinick, this is not fiscal responsibility. It is economic suffocation.

High taxes, he argues, do three disastrous things at once:

1. They crush growth before it starts

Small businesses never become medium ones. Medium businesses never become large ones. Capital formation dies in infancy.

2. They scare away investors

Why would a company like Nike build a factory where profits are taxed into extinction? No factories means no roads, no jobs, no skills transfer—just PowerPoint presentations about “potential.”

3. They exist to please creditors, not citizens

Vinick’s most devastating point is that these tax regimes often exist not because they work, but because External Lenders demand proof that governments can “raise revenue.” The result? High taxes that raise little, while killing the very economic activity that could have raised more.

His conclusion is blunt:

You cannot tax your way out of poverty when there is no growth to tax.

Now Cut to Nigeria: Same Script, No Applause

Fast-forward from fictional America to very real Nigeria.

The APC government has, over the years, perfected the art of borrowing. Foreign loans. Local loans. Loans for infrastructure. Loans for consumption. Loans, it seems, to pay for the interest on previous loans.

The justification is always the same:

“We need revenue.”

Enter Nigeria’s recent tax reforms.

We are told they will “broaden the tax base.” Which is political code for:

“More people who already have little will now have less, more efficiently.”

VAT tweaks. Compliance drives. Digital surveillance of small businesses. Tax thresholds that remain suspiciously low in a country where inflation has eaten the minimum wage for breakfast.

Sound familiar?

Nigeria, like the African economies Vinick described, is caught in a loop:

Borrow heavily

Promise creditors fiscal discipline

Raise taxes on a fragile economy

Kill growth

Borrow again

It is a treadmill powered entirely by paperwork.

The Solution We Already Watched on TV

Vinick’s prescription is not fashionable, but it is coherent:

Lower taxes to stimulate growth

Create space for businesses to breathe

Let investment build infrastructure, not loans

Replace dependency with productivity

This is not charity economics. It is supply-side logic applied to developing economies. The idea is simple enough to be dismissed by politicians, consultants and dangerous enough to work.

Without growth, tax revenue is a fantasy.

Without private investment, infrastructure is debt.

Without jobs, social policy is just sympathy with a logo.

Art 1, Reality 0

The tragedy is not that The West Wing proposed a solution. The tragedy is that a fictional senator articulated it more clearly than many real finance, coordinating ministers, Presidents, and Legistratures.

While Nigeria tightens tax screws and piles on debt, a 20-year-old TV drama calmly reminds us that you cannot milk a cow you have already slaughtered.

Art, it seems, did its job.

The rest of us are still arguing about implementation—while filling out loan applications.