Nigeria did not wake up one morning and become a country where bandits negotiate with governors. This is not an accident. It is a sequel.

The first instalment was Lawrence Nomanyagbon Anini. The current season features Bello Turji Kachalla. The difference is not in criminal audacity, but in state embarrassment. Anini embarrassed the Nigerian state. Bello Turji has institutionalised that embarrassment.

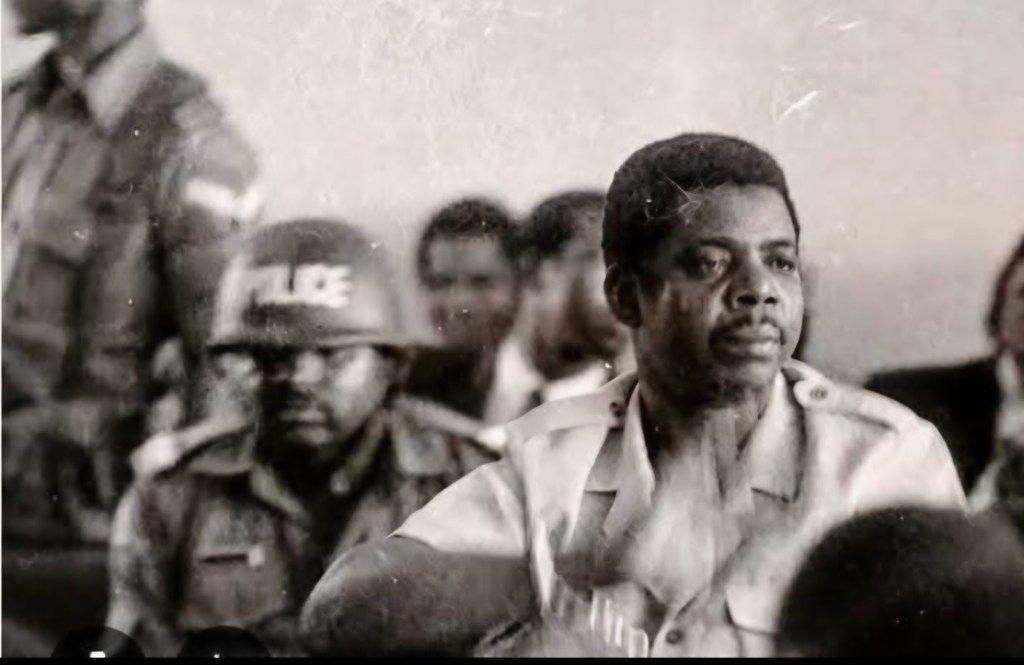

Anini: When Criminals Still Respected the Theatre of the State

In the mid-1980s, Anini terrorised Benin City with the confidence of a man who knew the police, knew the terrain, and knew that “security votes” were not yet a constitutional concept. He robbed banks, ambushed highways, assassinated policemen, and operated with such impunity that the state briefly outsourced policing to divine intervention and radio announcements.

Yet, for all his audacity, Anini never mistook himself for a co-equal sovereign. He did not negotiate ceasefires. He did not demand amnesty packages. He did not receive delegations. When caught, he was tried under the Robbery and Firearms (Special Provisions) Act, convicted, and executed by firing squad in 1987.

Brutal? Yes. Lawless? No. The Nigerian state still understood Section 4 of its coercive powers, even if it occasionally forgot Section 36 of fair hearing until after the fact.

Fast Forward: Bello Turji and the Birth of the Parallel Republic

Enter Bello Turji, who operates not as a criminal hiding from the state, but as a state negotiating with another state. He controls territory, levies taxes, grants safe passage, enforces curfews, and occasionally issues press-worthy ultimatums.

Under Section 14(2)(b) of the 1999 Constitution, “the security and welfare of the people shall be the primary purpose of government.” Bello Turji appears to have taken this provision personally — and implemented it selectively, for a fee.

The Nigerian government, meanwhile, appears to have reinterpreted Section 215 (control of the police) as “subject to availability, negotiation, and traditional rulers.”

The Criminal Justice System Takes a Coffee Break

Under Nigerian law, Bello Turji’s activities trigger a buffet of offences:

- Section 516, Criminal Code – conspiracy

- Section 402, Penal Code – armed robbery

- Section 1(2)(a), Terrorism (Prevention) Act – acts intended to seriously intimidate a population

- Section 1, Kidnapping Prohibition Laws (various states) – kidnapping for ransom

In theory, this should lead to arrest, prosecution, and punishment. In practice, it leads to stakeholder meetings.

At this point, the Nigerian criminal justice system resembles a court registry during strike season: officially open, practically unavailable.

Negotiation as Public Policy

When a state negotiates with a criminal who has not surrendered, has not disarmed, and has not submitted to jurisdiction, it is not practising conflict resolution. It is ceding sovereignty in instalments.

In Attorney-General of the Federation v. Abubakar (2007), the Supreme Court reminded us that constitutional powers are not ornamental. Yet here we are, watching governors behave like diplomats accredited to the Bandit Republic of North-West Nigeria.

One begins to wonder whether Bello Turji now enjoys implied immunity under a doctrine yet to be invented: Bandit Immunity (Negotiation Pending).

The Satirical Irony Nigeria Refuses to Acknowledge

Anini was captured, tried, and executed without negotiations. Bello Turji is discussed, analysed, pleaded with, and occasionally blamed on “root causes.”

Nigeria has evolved — not into a failed state, but into a selectively functional one, where:

- Laws apply firmly to petty thieves,

- Swiftly to protesters,

- Brutally to journalists,

- And negotiably to men with machine guns.

In R v. Princewill (1963), Nigerian courts affirmed that no one is above the law. Bello Turji appears to be testing whether no one includes people with territorial control.

From Warning Sign to Confirmation Notice

Anini was a warning sign — a flare in the dark indicating police rot, institutional weakness, and elite complicity. Bello Turji is the confirmation notice: stamped, sealed, and counter-signed.

Nigeria is not yet a failed state. It is something more Nigerian: a state that still writes laws, still quotes the Constitution, still swears officials into office — but negotiates enforcement depending on the calibre of the gun involved.

Conclusion: The Law Has Not Died — It Has Been Deferred

In Nigerian jurisprudence, justice delayed is justice denied. In Nigerian security policy, justice negotiated is justice outsourced.

Until the state reclaims its monopoly of force — not rhetorically, not ceremonially, but operationally — Bello Turji will not be an aberration. He will be a precedent.

And as every lawyer knows, precedents are dangerous things when left unchallenged.