In the sober textbooks of international relations, diplomacy is presented as a rational enterprise conducted by trained professionals in pinstripes, armed with briefing notes, institutional memory, and a pathological fear of saying anything interesting. In practice, however, there are two kinds of ambassadors: career and non-career.

Career ambassadors are civil servants. They rise through the foreign service, rotate through postings, and run embassies with all the emotional warmth of a medium-sized filing cabinet. Their job is continuity, not chemistry. You send them to Belgium, Denmark, or another European capital where relations are steady, predictable, and nobody wakes up at 3 a.m. to check the president’s social media feed.

Non-career ambassadors, on the other hand, are something else entirely. They are personal envoys. Political appointees. Friends, donors, fixers, loyalists. They are appointed outside the civil service rules as rewards for service—electoral, financial, or emotional. Their qualification is not diplomatic finesse but proximity to power. They don’t so much represent the state as embody the vibes of the leader who sent them.

This distinction matters—especially when dealing with Donald J. Trump.

Until recently, the UK ambassador to the United States was a career diplomat, doing the usual job of smoothing relations while quietly documenting chaos. That arrangement ended abruptly when confidential emails describing the Trump administration as dysfunctional—accurate but unflattering—were leaked. Trump, who elevates personal feelings above constitutional architecture, responded as expected: fury, sulking, and banishment.

At the time, Britain had just exited the European Union and desperately needed favourable trade relations with the world’s other major power. Unfortunately, that power was being run less like a republic and more like a family business with nuclear weapons. Normal diplomacy would not work. Trump does not do “institutions”; he does relationships.

Enter Peter Mandelson.

The choice was, in hindsight, revealing. Mandelson is not a diplomat. He is a political operator, a survivor, a man whose biography reads like a glossary of New Labour intrigue. In other words, exactly the sort of “character” Trump instinctively understands. Where career diplomats bring briefing notes, Mandelson brings backstories.

Trump’s world is small and circular. It is built on networks of mutual acquaintances, shared dinners, overlapping scandals, and the comforting belief that everyone important knows everyone else important. In that ecosystem, Mandelson made sense.

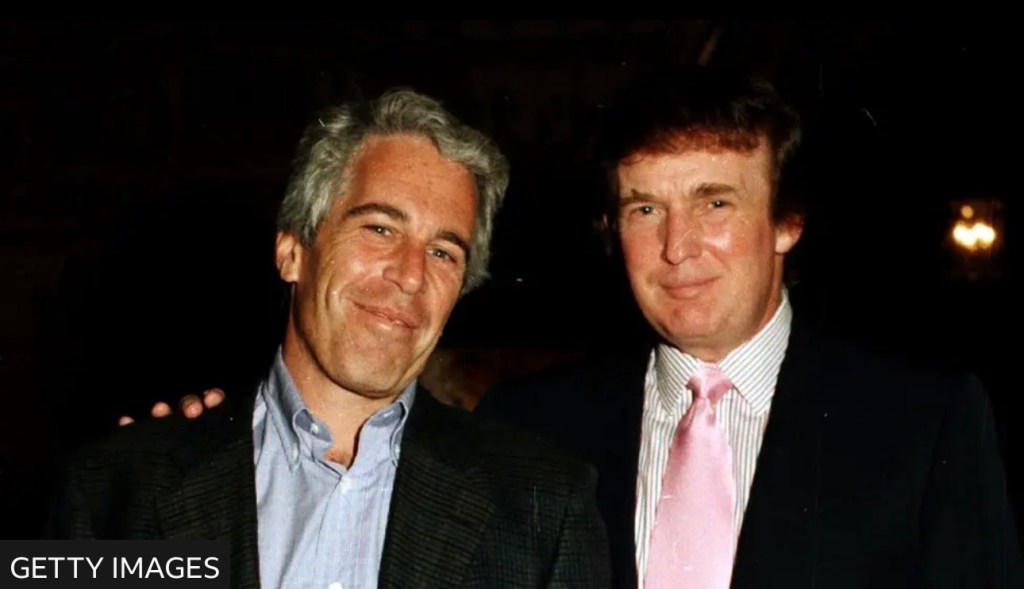

Trump’s longtime associate and friend was Jeffrey Epstein—a convicted sex offender and flamboyant rogue financier. Epstein, in turn, moved in elite social circles where Mandelson was a familiar presence. Six degrees of separation? Hardly. More like two awkward dinner invitations and a shared contact list.

From a cold, transactional perspective, the calculation was obvious: Mandelson might have access where others would be ignored. He might speak Trump’s language. He might get the phone answered.

And for a while, that probably seemed clever.

But history has a way of turning “pragmatism” into “catastrophic judgment”.

With the benefit of hindsight—and a mountain of emails, testimonies, flight logs, and reputational wreckage—the Epstein connection has become radioactive. What once looked like savvy realpolitik now resembles recklessness. The sort of recklessness that comes from confusing “knowing people” with “being untouchable”.

The nomination of Mandelson is now widely regarded as a serious error. Not merely embarrassing, but destabilising. It has dragged old associations into the present, handed opponents a moral cudgel, and placed the Labour government in a defensive crouch over decisions it would rather forget.

Diplomacy, we are told, is about judgment. About knowing not just who can open doors, but which doors should never be approached in the first place. Britain needed an envoy to deal with Trump’s America. What it got instead was a reminder that when diplomacy is reduced to personal chemistry, the hangover can threaten the government itself.

In international relations, vibes are not a strategy. And rogues, however charming, eventually leave fingerprints.