History, when irritated, develops a sharp tongue.

A minority once sailed into other people’s lands, drew borders with imperial indifference, renamed mountains, and installed themselves as the managerial class of entire continents. The model was perfected by the British Empire—a project so vast it required both a navy and a filing system.

The architecture was clear: conquer, consolidate, codify. Extract resources. Institutionalise hierarchy. Occupy the commanding heights of politics, commerce and culture. When labour was required, import it. When dissent arose, administer it.

After the Second World War, when Britain was exhausted and indebted, it turned—logically—to the empire it had built. The arrival of the HMT Empire Windrush in 1948 was not an invasion; it was labour policy. Those passengers were British subjects invited to rebuild bombed-out cities, staff hospitals, and drive the buses that kept the capital moving.

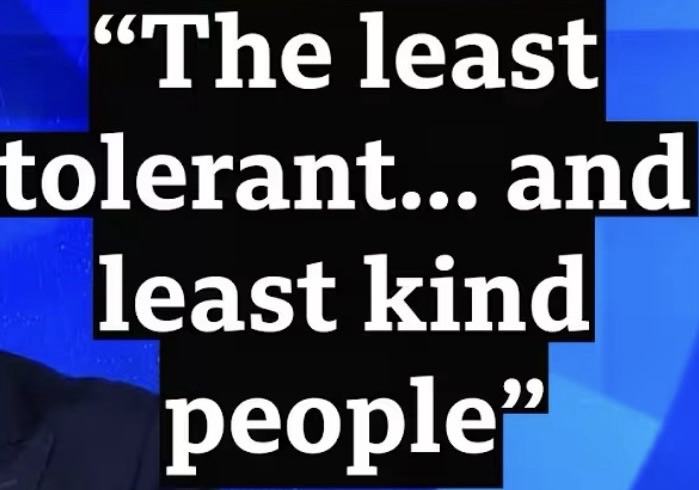

Fast forward to the present. A new anxiety stalks the commentariat. A billionaire immigrant frets that migrants—often in low-paid, precarious work—are somehow “colonising” Britain from below. Apparently, the cleaner is a geopolitical strategist. The care worker is orchestrating regime change between tea breaks.

Let us add names to the satire.

Take Jim Ratcliffe, Britain’s wealthiest man, who quite sensibly resides in Monaco, a jurisdiction celebrated for its Mediterranean climate and discreet tax regime. One does not begrudge a billionaire his sunshine. But there is a certain operatic flourish in lamenting national decline while domiciled in a microstate whose fiscal model depends on not being Britain.

This is not a personal attack. It is a structural observation. When capital is globally mobile but labour is politically suspect, something is inverted.

Meanwhile, political entrepreneurs have discovered that race and immigration are far more rhetorically profitable than supply-side reform. Reform UK—a company as much as a party in its corporate structure—has built an insurgent brand on cultural grievance, promising to restore sovereignty, shrink migration, and detoxify the national bloodstream.

The Conservative Party, facing electoral erosion, has oscillated between technocratic management and rhetorical escalation. One week: net migration targets. The next: small boats. The week after: emergency legislation. It is a choreography of urgency.

But here is the inconvenient macroeconomic footnote: none of this lowers grocery bills.

Britain’s cost-of-living crisis is driven by energy shocks, anaemic productivity growth, housing supply constraints, post-Brexit trade frictions, and stagnant real wages. These are structural issues requiring industrial strategy, planning reform, investment in skills, and fiscal clarity. They are not resolved by reciting immigration figures at a lectern.

When households worry about rent, mortgages and energy bills, the politically efficient move is to offer an identifiable antagonist. Migrants are visible. Global supply chains are not. The nurse from Lagos is easier to visualise than the bond market.

The paradox is almost theological. The same political tradition that once managed an empire—moving capital, goods and people across continents—now trembles before delivery riders and junior doctors with foreign surnames. Colonisation, properly defined, involves conquest and institutional domination. It does not involve twelve-hour shifts on minimum wage.

If low-paid workers are “running the country from behind,” then sovereignty has migrated to the warehouse floor.

There is also an irony in billionaires warning of demographic takeover while benefiting from globalisation’s open circuits. The modern British economy—finance, higher education, healthcare, hospitality—runs on international labour. To denounce that labour without replacing it with a credible productivity strategy is not policy. It is theatre.

And theatre has its uses. It animates rallies. It fills airtime. It converts anxiety into applause. But it does not rebalance the housing market. It does not raise real wages. It does not repair public services hollowed out by a decade of fiscal restraint.

The deeper truth is uncomfortable: Britain’s economic model has struggled to generate broad-based prosperity. When growth falters, redistribution becomes fraught. When redistribution is fraught, identity becomes combustible.

So the coloniser who now cries “colonisation” performs a familiar trick: rebrand economic malaise as cultural siege. It is tidier that way. No need to explain productivity graphs or capital formation. Simply point to the newcomer and declare a national emergency.

History, again, smiles thinly.

An empire once redrew the world and sat at its apex. Its descendants now debate whether bus drivers are executing a master plan. The problem is not that migrants are running Britain. The problem is that too many politicians are running from economics—and sprinting toward grievance instead.

In the end, the cost of living is not paid in rhetoric. It is paid at the till. And no amount of imperial nostalgia will make the receipt shorter.