When Ronald Reagan spoke of America as a “shining city on a hill,” he wasn’t merely offering a line for a campaign rally. He was invoking a moral architecture. The metaphor carried theological undertones and constitutional confidence. America was not just powerful; it was exemplary. A beacon. A sermon in brick and mortar.

The world believed him.

More importantly, Americans believed him.

They believed they lived above the fray of history — above the coups, above the strongmen, above what Donald Trump would later crudely label “shitholes.” The United States was different. Incorruptible. Enlightened. A republic of laws, not men.

And at the centre of this civic theology stood a document: the United States Constitution.

It was treated less as a political compromise drafted in Philadelphia and more as a secular tablet handed down by the Founding Fathers — Washington, Madison, Jefferson — prophets in powdered wigs.

Of course, the Constitution began imperfectly. Its blessings did not apply to everyone at inception. Enslaved people were counted but not protected. Women were governed but not enfranchised. Indigenous nations were displaced, not consulted. The shining city had zoning restrictions.

Yet here is the uncomfortable truth: despite its contradictions, the American experiment proved astonishingly durable. It generated prosperity on a scale unseen in modern history. It underwrote global institutions. It projected a version of rule of law that — while inconsistently applied — shaped international norms.

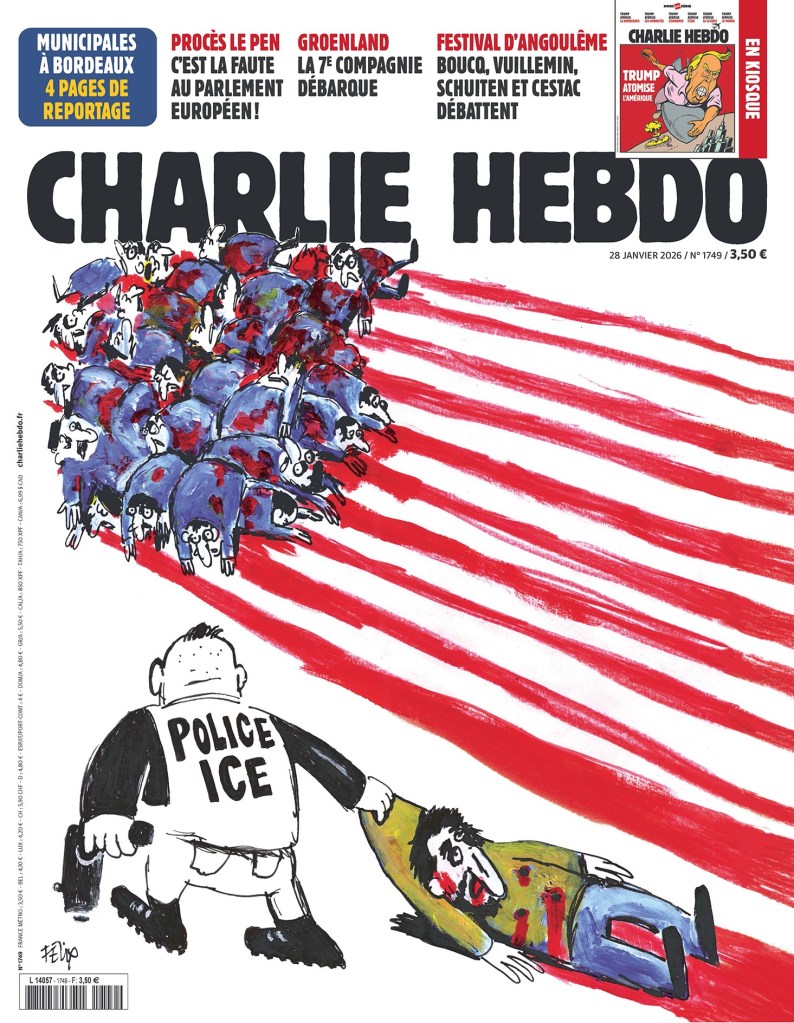

Rome ruled through legions. Britain ruled through naval supremacy. America ruled through a combination of aircraft carriers, Hollywood, the dollar, and the promise that law constrained power.

For decades, large-scale official corruption was something Americans associated with “other countries.” Military coups? Banana republics. Election manipulation? Developing nations. Leaders refusing to concede defeat? That was for fragile democracies.

Nigerians fled to America not merely for economic opportunity but for institutional predictability. You might hustle in Lagos, but you trusted the courts in Washington. The myth of American incorruptibility was export-quality.

Then came January 6.

The insurrection at the Capitol — the modern Reichstag moment — shattered the illusion that American democracy was immune from the pathogens of personality cults and mob politics. The mob was not foreign. It was homegrown. It wore flags and carried scripture. It believed it was saving the republic while desecrating it.

In other countries where presidents toyed with insurrectionary impulses, consequences followed. In Brazil, former president Jair Bolsonaro faced prosecution after chaos in Brasília. In South Korea, presidents such as Park Geun-hye have gone to prison. The system asserted itself with ruthless clarity: no one is above the law.

America, however, hesitated. Prosecuted, yes. Indicted, certainly. But politically rehabilitated? Also yes. The mask slipped — not because America had flaws, but because the flaws proved survivable without immediate institutional collapse.

The shining city turned out not to be marble but clay — impressive from afar, fragile up close.

And yet, to declare America “Hitler’s Germany with an American accent” is emotionally satisfying but analytically lazy. Adolf Hitler dismantled institutions with terrifying efficiency. The American system — bruised and battered — has not been dismantled. Courts still rule against presidents. States still certify elections. Journalists still publish. Opposition still campaigns.

The ugliness is visible, yes. The tribalism, the billionaire class openly flexing influence, the media ecosystems feeding grievance — all real. But so is resistance.

Perhaps the greater shock is not that America has clay feet. It is that Americans are discovering what much of the world already knew: no democracy is self-executing. No constitution is divine. No republic is permanently inoculated against demagoguery.

The “shining cities” of today are not confined to one hill in North America. They are scattered — in Brussels with its bureaucratic order, in London with its centuries of parliamentary adaptation, in Kigali with its improbable post-conflict reconstruction. Each imperfect. Each striving.

America’s tragedy is not that it was never shining. It did shine. It still shines in places — in laboratories, courtrooms, universities, civil rights movements, and immigrant ambition.

The tragedy is that Americans believed the shine was permanent.

Reagan’s metaphor was aspirational. Trump’s rhetoric was confrontational. Between the two lies the truth: a republic is not a hilltop monument; it is a maintenance project.

The city does not shine by proclamation. It shines by practice.

And practice, like democracy, is daily work.