It’s not often in Nigerian politics that a man grows into a role instead of shrinking under it, but Adams Oshiomhole seems to have done the political equivalent of fine wine—improving with age, and thankfully without the usual bitterness. I must confess, I find Oshiomhole a far better senator than he ever was a governor.

As governor of Edo State, Oshiomhole was like a man who discovered government machinery and decided it was a personal gym—every day was a new fight. He fought godfathers, teachers, pensioners, potholes, and sometimes even microphones. He ruled with the energy of a man who had too much Nescafé and too little patience. His speeches were half-governance, half-boxing commentary, and one always expected him to end each policy announcement with, “Let’s get ready to rumble!”

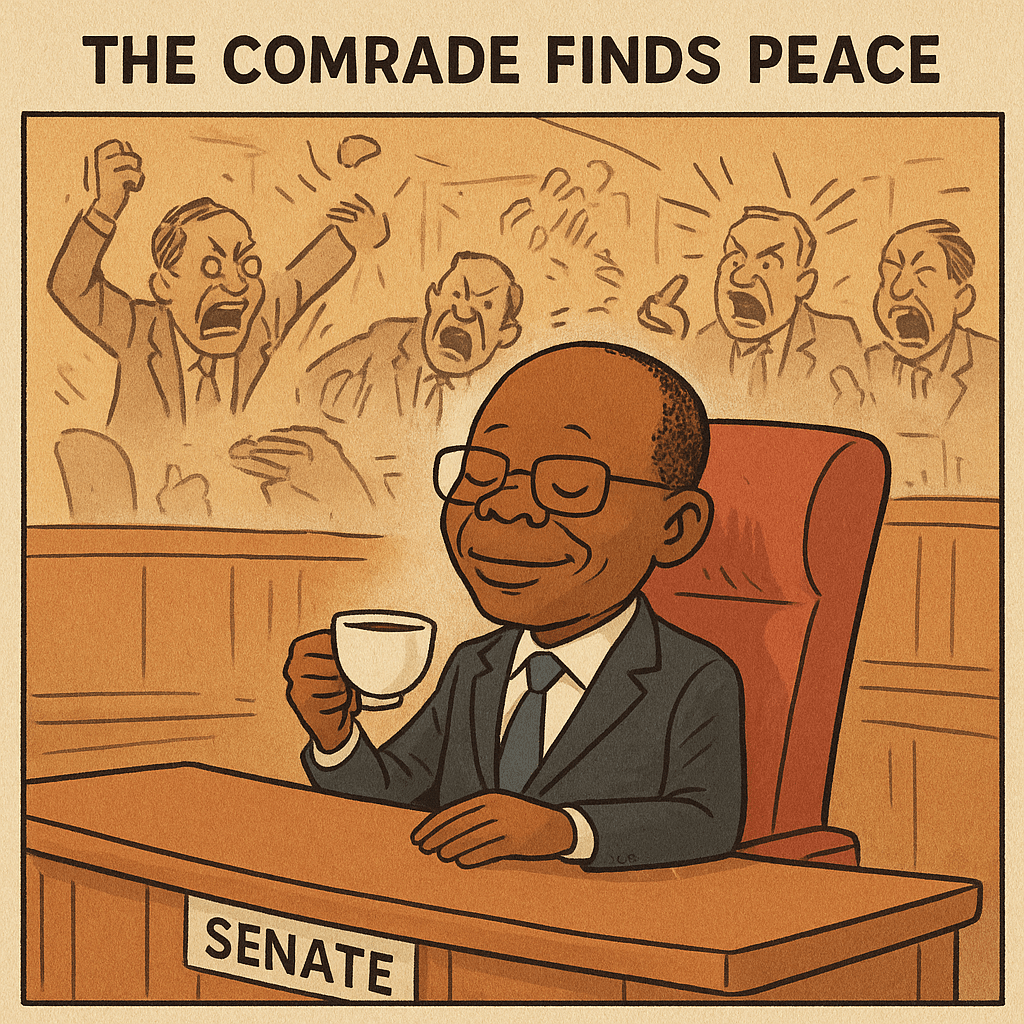

But as senator, something wonderful happened. The man mellowed. He now speaks with a surprising calm, as though the red chamber’s air-conditioning finally cooled the revolutionary in him. Instead of swinging verbal machetes, he now delivers policy analyses with the poise of an academic in a committee hearing—albeit one who might still call the Vice President “my comrade-in-progress.”

Maybe the secret is that the Senate suits him. The Senate is less about fixing roads and more about fixing grammar in motions. Less about construction sites, more about construction of sentences. And if there’s anything Oshiomhole loves as much as a good political brawl, it’s a long sentence with “my dear colleagues” somewhere in it.

His recent performances in plenary are worthy of note. He speaks with the rare mix of factory-floor grit and policy polish. It’s as if Karl Marx took a public speaking course in Auchi. When others ramble, Oshiomhole punctures pretence with humour and statistics—like a man who knows the system because he once wrestled it in a wrestling ring called Edo politics.

Ironically, the same bluntness that made him a controversial governor now makes him one of the Senate’s more refreshing voices. He doesn’t pretend to be diplomatic—he just calls nonsense what it is, usually with a smile that says, “You may not like it, but you know I’m right.”

Maybe Oshiomhole found what most Nigerian politicians never do: perspective. Governorship is theatre; the Senate, a debate club with microphones. And for once, he’s not swinging the mic like a cudgel—he’s using it like a pen.

If he keeps this up, he may go down as one of the few Nigerian politicians whose career actually improved after the executive seat. In a country where most ex-governors enter the Senate to nap, Oshiomhole entered it to talk sense.

Who knows—maybe we’ll soon hear he’s starting a mentoring class titled “From Agbero to Aristotle: The Comrade’s Guide to Political Maturity.”