For all the heat surrounding Nnamdi Kanu’s legal troubles, one thing must be said plainly: the supposed legal disagreement that some have tried to elevate into a principled debate has no grounding in any known law. It was, at best, courtroom revisionism; at worst, gaslighting in broad daylight.

Let’s be clear. Kanu was not targeted simply because he demanded a Biafran state. Nigeria has endured louder agitators. He was not prosecuted for the dream, but for the behaviour that stood in front of it—behaviour that revealed a worldview shaped not by statesmanship but by spectacle. His conduct in court reflected the very attitude he projected toward the Nigerian state and even toward the people he claimed to speak for. To downplay that is to downplay the pain of those who followed him in sincerity.

And this is the true tragedy: few political actors in the South-East have ever possessed the kind of raw influence and political space that Kanu did. The governors of the region were, in comparison, Lilliputians. He enjoyed mass support, rousing emotional capital, and a platform that could have changed the region’s political trajectory for a generation.

He could have used his popularity to seize legitimate political power across the South-East. He could have built a formidable referendum movement, or governed one of the states to demonstrate—practically—what a new, more just Biafran vision might look like. He could have done what Dim Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu did before declaring secession: convene elders, intellectuals, industrialists, and traditional rulers. He could have exhausted the peaceful routes, negotiated like a man prepared for outcomes, and only after all else failed, consider what next.

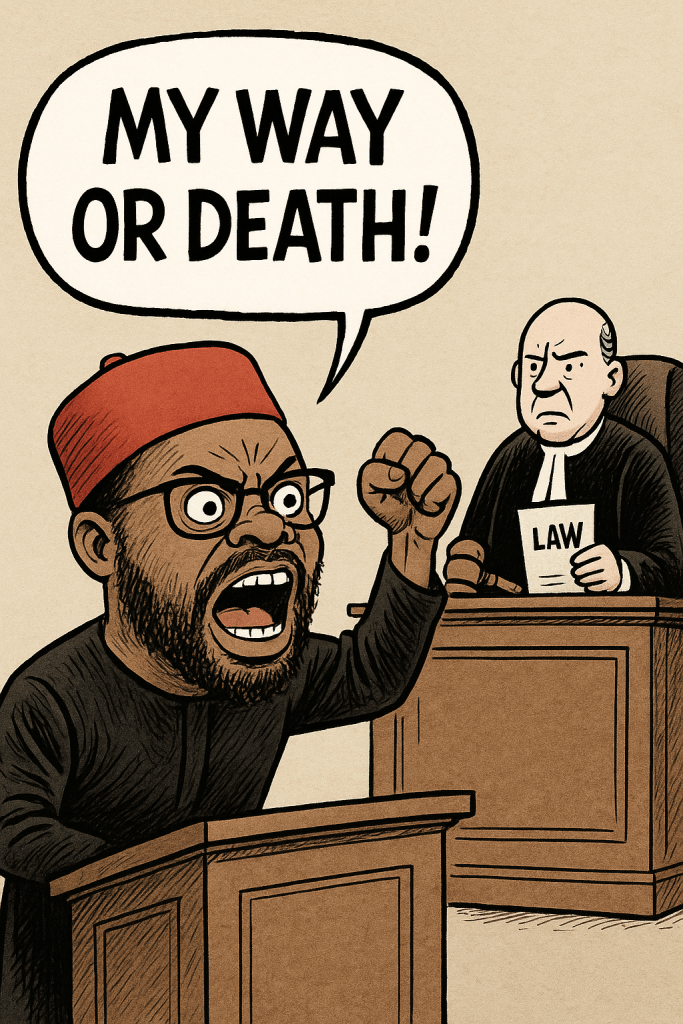

Instead, the approach became absolute. There was no Aburi. No roundtable. No coalition of thought. No patience for dissenting opinions within the movement. It was a politics of ultimatum: “my way or death.” And such a model has never birthed a stable nation—only personal fiefdoms and permanent agitation.

If Biafra were re-created today under such leadership, it risks resembling South Sudan: a nation where the price of independence became the inheritance of conflict, and where liberation was reduced to a vehicle for private ambition. There is, sadly, a thin line between Sudan and South Sudan—and the sacrifices of the people can easily become a wasted, circular struggle.

Compounding the problem is the vacuum created when the political leaders of the South-East, including voices like Osita, abdicated their responsibilities. Leadership spaces do not remain empty. They get filled—often not by the best, but by the loudest.

And so we arrive at the present crossroads.

Nigeria’s political contradictions remain, but the path forward cannot be built on the politics of personality or performance. It cannot rely on emotional crescendos with no institutional grounding. As has been rightly argued, the next chapter requires seriousness, strategy, coalition-building, and a reconstruction of the political muscle that once made the South-East a centre of excellence.

On that path, I agree wholeheartedly. There is no liberation without leadership, no freedom without structure, and no new dawn built on the foundations of impulsive absolutism.

The region—and indeed the nation—deserves better than theatre.