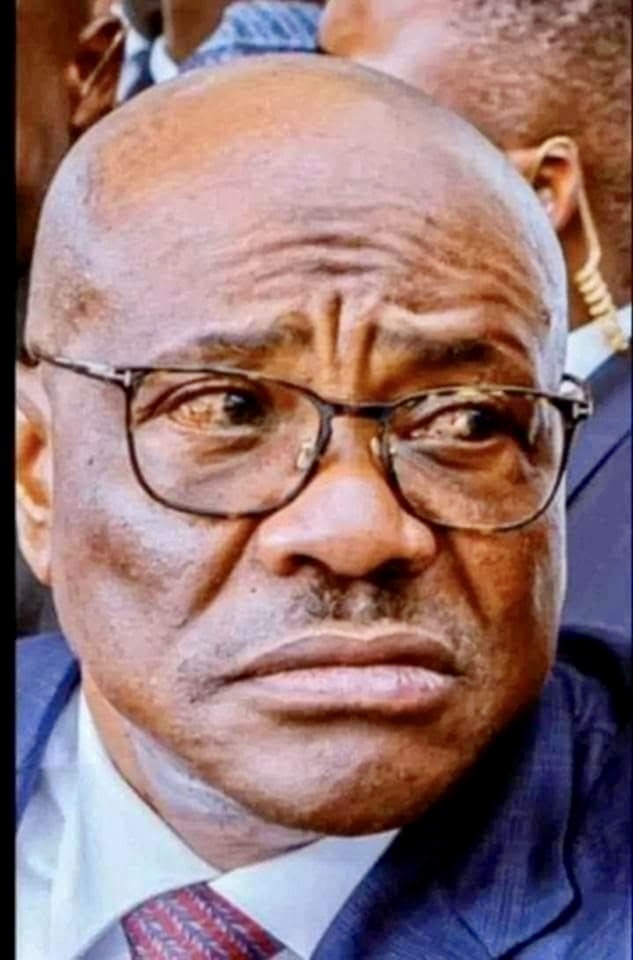

The Kingsley Moghalu’s article on X is serious, sober and correct—which in Nigeria automatically makes it suspicious. It diagnoses Nigeria’s problem as the capture of power by a political elite obsessed with “primitive accumulation.” I disagree slightly. What we have is not primitive accumulation; it is advanced, sophisticated, PhD-level accumulation. These people have turned looting into a fintech product.

Kingsley Moghalu laments the exclusion of the “real elite”—intellectuals, professionals, technocrats like himself obviously. This is unfair. Nigeria has never excluded intellectuals. We merely assign them appropriate national roles: writing op-eds, attending conferences in hotels with intermittent electricity, and explaining on X, why things are collapsing again. Governance is too important to be left to people who read footnotes.

We are told that up to the 1970s Nigeria was progressing. True. That was before we discovered oil, easy money, and the revolutionary idea that you can be spectacularly incompetent and still be in charge. Progress was moving nicely until we realised that planning is stressful, while sharing money is relaxing and builds “structure.”

The military era, we are reminded, tried to rejig the country and even built infrastructure. Yes. Soldiers, for all their faults, had a simple worldview: command, obey, build road. Civilians complicated things with concepts like accountability, ideology and manifestos—documents which, in Nigeria, are largely fictional literature.

Then came 1999 and OBJ, armed with technocrats in one hand and political entrepreneurs in the other. A delicate balancing act, like holding a copy of the World Bank report while shaking hands with your village meeting chairman. Unsurprisingly, the entrepreneurs won. They always do. Technocrats ask, “Does this policy work?” Political entrepreneurs ask, “Who is on the list?” Nigeria, being a humane country, chose inclusion.

By 2015, the political entrepreneur class was no longer sharing power; it was power. Thinkers became persona non grata, which is Latin for “please keep quiet, you are disturbing the sharing.” Ambassadors were left unappointed for two years because, frankly, embassies don’t vote. Besides, what exactly do ambassadors do? Talk? Think? Explain Nigeria to foreigners? Abeg.

The article mourns the absence of serious thinking. This is inaccurate. Nigeria has plenty of thinking—just not about governance. We think deeply about elections, court orders, zoning formulas, party defections, and which scandal will blow over by Monday. Governance is a side hustle.

The call for an “age of enlightenment” is noble but ambitious. Enlightenment requires light. Light requires electricity. Let us not get ahead of ourselves. Independent institutions, rule of law, transparency—excellent ideas, but they lack political structure. You cannot deploy them during elections.

In conclusion, Nigeria has not failed because we rejected technocrats. We simply made a strategic decision to prioritise politics over governance, survival over progress, and noise over thinking. Until enlightenment can be monetised, securitised, and shared at ward level, the political entrepreneur will remain our most successful export.

And honestly, in a country where incompetence is renewable and outrage is seasonal, that might just be our most stable institution yet.