There is an old English saying that “sometimes there is a method to madness.” It is usually deployed to rescue chaos from meaning, to suggest that beneath the noise there is a plan. With Donald Trump, the phrase deserves to be examined carefully—because while the madness is obvious, the method is thinner than advertised.

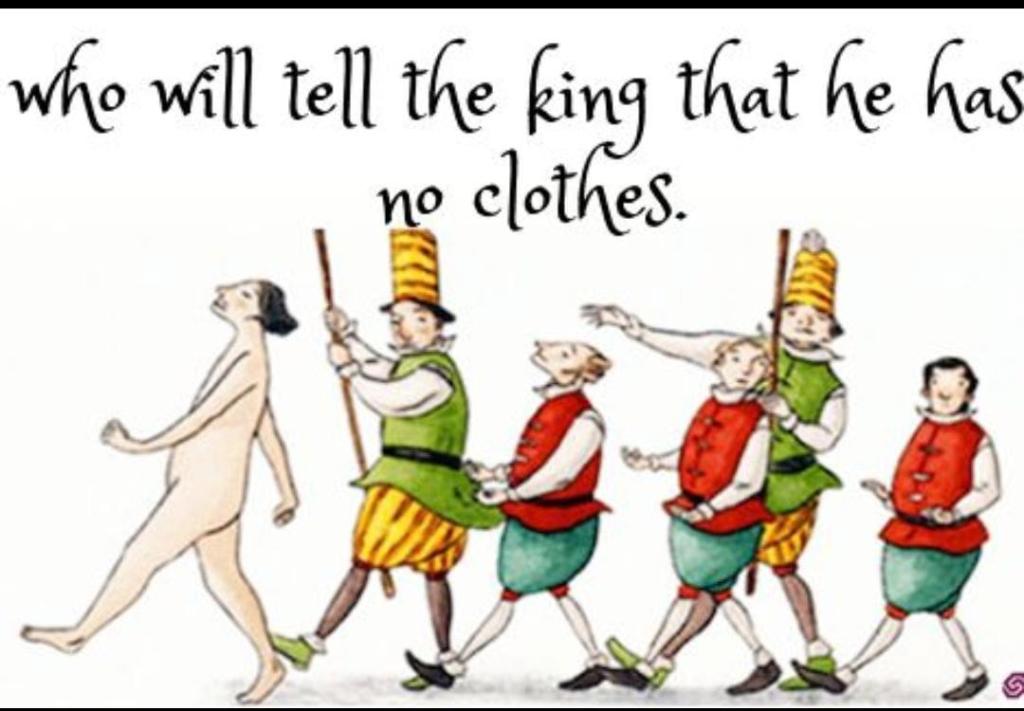

Trump is certifiably mad in the non-clinical, everyday sense of the word. Not “diagnosable,” not “DSM-V,” just the garden-variety political madness that believes personality can substitute for institutions, bluster for legitimacy, and volume for law. He genuinely appears to think that the United States—and by extension the world—can be bent in one direction or another by force of his will, his moods, his grudges, and his social-media account.

This belief has produced frightful and dangerous consequences, both domestically and internationally. Norms are treated as inconveniences, alliances as protection rackets, treaties as bad deals signed by stupid people, and institutions as enemies when they fail to applaud loudly enough. The presidency is not seen as an office embedded in a constitutional order, but as a personal franchise temporarily housed in the White House.

Yet here lies the paradox—and the saving grace.

None of this will outlive him.

Trump’s great failure is not merely moral or intellectual; it is institutional. By bypassing institutions, by scorning process, by treating law as a suggestion rather than a framework, he has ensured that his actions are built on quicksand. They are not anchored in durable consensus, legislative buy-in, treaty obligations, or institutional memory. They exist largely as extensions of his personality. When the personality exits the stage, the props collapse.

History is unforgiving on this point. Enduring change does not rest on tantrums or strongman theatrics; it rests on institutions. The League of Nations failed precisely because it lacked sufficient buy-in and enforcement mechanisms. Its successor, the United Nations, emerged not simply from presidential willpower but from persuasion, negotiation, and the slow cooking of protocols, conventions, and shared interests. Even its flaws are institutionalised—and therefore persistent.

Trump does not, and perhaps cannot, operate this way. He is constitutionally incapable of inviting genuine buy-in. A sole trader by temperament, he mistrusts partnerships, despises constraints, and sees compromise as weakness. Coalitions require patience; institutions require humility; legitimacy requires limits. These are not his natural habitats.

Ironically, this is good news for the world.

Because what is not institutionalised cannot endure. Executive orders can be reversed. Norms smashed by one administration can be rebuilt by the next. Damage may linger—there are always residual remnants when vandals leave a building—but without sustained political and institutional reinforcement, those remnants eventually decay.

History again provides perspective. Hitler’s regime was cataclysmic, but it left no enduring constitutional legacy worthy of emulation—only ruins, taboos, and lessons. The Third Reich did not survive its author. Neither will Trumpism in its pure form survive Trump. Personal rule is always brittle; institutions, even battered ones, are stubborn.

So yes, there is a method to Trump’s madness—but it is a self-defeating one. By refusing to embed his agenda within institutions and principles, he has guaranteed its impermanence. Time, that most reliable constitutional lawyer, will turn on him. And when it does, much of what he wrought will evaporate with him.

The world may yet pay a price for the interlude. But in the long arc, personality cults lose; institutions endure. And that, at least, is the method by which madness ultimately defeats itself.