A sober reflection on General Murtala Ramat Mohammed requires a careful separation of verifiable history from rumour, memory from myth, and institutional responsibility from individual culpability. Fifty years after his assassination, he remains one of Nigeria’s most mythologised leaders—celebrated as a nationalist reformer, yet inseparable from some of the most violent and turbulent episodes in the country’s history.

The July 1966 Counter-Coup and the Politics of Retaliation

Murtala Ramat Mohammed first entered national prominence during the July 1966 counter-coup. The January 1966 coup led by mostly young officers of Igbo extraction had overthrown the civilian government and resulted in the killing of leading northern political and military figures, including Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa and Northern Premier Ahmadu Bello.

The July counter-coup was a violent reprisal by northern officers. It resulted in the killing of the Head of State, Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, and widespread killings of officers of eastern origin. Among the key northern officers was Murtala Mohammed, widely regarded as one of the leading figures of the revolt. Lieutenant Theophilus Danjuma was directly involved in the arrest of Ironsi.

Accounts suggest that the emotional and political trauma of the January coup—particularly the killing of Ahmadu Bello—profoundly shaped Mohammed and his cohort. Bello had encouraged northern participation in the Nigerian Army as part of a strategy to close educational and institutional gaps between regions. Many northern officers saw themselves as personally loyal to him. Whether Mohammed’s motivations were ideological, regional, or retaliatory, the counter-coup entrenched the regional fracture within the Nigerian state.

There are long-standing claims that some northern officers initially contemplated secession before being dissuaded—possibly by diplomatic intervention, including from British representatives. While documentation remains incomplete, the episode underscores how fragile the federation had become by mid-1966.

Pogroms and the Descent into Civil War

Following the counter-coup, pogroms erupted across northern Nigeria, targeting Igbo civilians. Tens of thousands were killed; many more fled eastward. The military government in Lagos struggled to contain the violence. The Eastern Region, under Lieutenant Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, increasingly lost confidence in the federation’s viability.

The massacres and breakdown of trust were direct precursors to the declaration of Biafra in May 1967 and the ensuing civil war. Responsibility for the pogroms cannot be reduced to one individual, yet Mohammed’s role in the counter-coup situates him within the chain of events that destabilised the state beyond repair.

The Civil War: Battlefield Leadership and Controversy

During the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), Mohammed commanded the 2nd Division of the Nigerian Army. His west-to-east advance recaptured Mid-Western territory and pushed Biafran forces back across the Niger.

However, the campaign remains controversial. In October 1967, following the recapture of Asaba, large numbers of unarmed male civilians were killed in what many historians describe as a massacre. Debate persists regarding the chain of command and the extent of Mohammed’s knowledge or responsibility. Nonetheless, as divisional commander, operational accountability rested with him.

His subsequent attempt to cross the Niger and capture Onitsha from the riverine axis was poorly coordinated and resulted in heavy casualties. The operation’s failure led to his recall from frontline command. This episode fed a perception—fair or otherwise—of impetuous decision-making and insufficient adherence to higher command directives.

It is important to state that civil wars are environments of breakdown, fear, and brutalisation. Yet the absence of transparent post-war inquiry into battlefield conduct has left unresolved questions that continue to shadow historical memory.

The 1975 Coup and Reformist Zeal

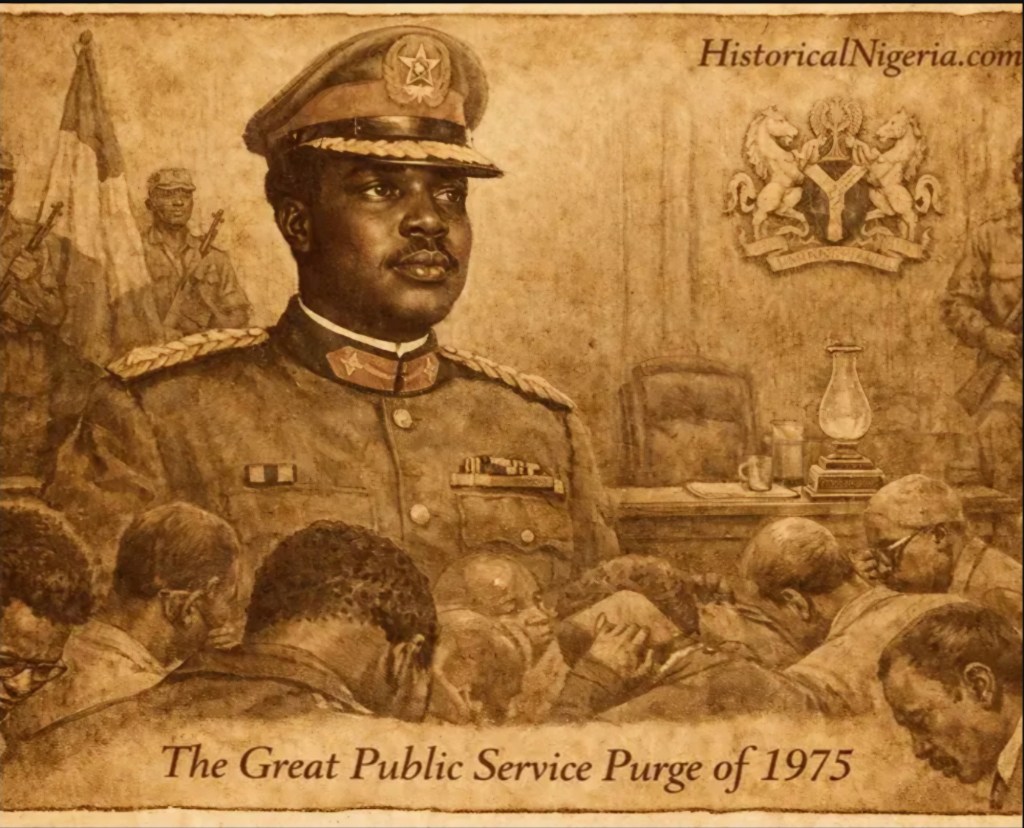

In July 1975, Mohammed led a bloodless coup that overthrew General Yakubu Gowon while Gowon was abroad. The coup was widely welcomed domestically. Gowon’s regime had lost credibility amid economic mismanagement, delays in returning to civilian rule, and perceived complacency.

As Head of State, Mohammed moved swiftly. His government:

- Purged thousands of civil servants and military officers on grounds of corruption or inefficiency.

- Announced a timetable for return to civilian rule.

- Initiated the creation of new states to rebalance federal power.

- Began the relocation of the federal capital from Lagos to what would become Abuja.

- Pursued a more assertive foreign policy, especially in support of African liberation movements.

His decisiveness earned admiration. For many Nigerians, he embodied energy, patriotism, and intolerance for bureaucratic decay. Yet the mass purge of the civil service, executed rapidly and often without transparent due process, generated institutional trauma and accusations of arbitrariness.

The decision to move the capital inland was framed as geographic neutrality and administrative necessity. Critics, however, interpreted aspects of his defence and administrative restructuring as reinforcing northern strategic advantage. As with much of his legacy, interpretations remain divided.

Assassination and Canonisation

On 13 February 1976, Mohammed was assassinated in an abortive coup led by Lieutenant Colonel Buka Suka Dimka. His tenure had lasted just over six months.

His death transformed him into a national symbol. Airports, institutions, and public spaces were named in his honour. The abruptness of his rule allowed admirers to project onto him the promise of unrealised reform. The narrative of the incorruptible reformer hardened into orthodoxy.

A Balanced Historical Assessment

Half a century later, a sober evaluation must acknowledge several truths simultaneously:

- He was a central actor in a violent counter-coup that deepened Nigeria’s ethnic fracture.

- He commanded forces during controversial military operations whose human costs remain insufficiently interrogated.

- He demonstrated administrative boldness and reformist urgency upon assuming power.

- He governed briefly, leaving a legacy shaped as much by symbolism as by measurable institutional outcomes.

History should neither demonise nor sanctify. The transformation of Mohammed into an untouchable icon has arguably inhibited rigorous public discourse about military interventionism, accountability during civil conflict, and the long-term effects of abrupt administrative purges.

The broader question is institutional: Why does Nigeria continue to romanticise military rule? The elevation of strongmen, particularly those cut down early, reflects a recurring national frustration with civilian governance. In that sense, Mohammed’s afterlife in public memory tells us as much about Nigeria’s political psychology as about the man himself.

Fifty years on, the task is not to dethrone him from public memory but to situate him properly within history—recognising courage and resolve where they existed, and confronting violence and error where they occurred. Only then can memory mature into understanding.